Muddled Thinking on Inflation

Let's cut through the muddled thinking on inflation, debt, interest rates.

Sadly, I learned today that 231 economists have been hospitalized with neck and spine injuries sustained when they suddenly and without warning flipped from worrying about deflation to worrying about inflation when the Labor Department reported the CPI was up 4.2% in April. When questioned, the head of orthopedic surgery at Boston General explained, “The damage appears to be concentrated between cervical vertebrae C1 and C2, used when a person suddenly changes their mind. (See the graphic below.) In this case, the movement was just too quick, damaging the connective tissue, made worse by the fact that many of the sufferers had never actually changed their minds before.”

The good news is that the patients are all economists, not plumbers or carpenters, so there should be no negative impact on GDP.

Muddled Thinking about Inflation

Muddled thinking about inflation is also driving wild swings in asset prices from one day to the next. Frightened people analyze word maps of Federal Reserve press releases looking for signs of optimism or pessimism and pounce on each new data point as if it contained the key to seeing the future. In this environment it is difficult for investors to make sensible decisions about their portfolios.

There is no single data point that would change my mind about either the state of the economy or how I want to structure my portfolio—not last month’s CPI, not last month’s new jobs number, not last quarter’s GDP report. After all, they all report what has already happened, making me want to ask anyone surprised by the number, “weren’t you there?” And it’s not important whether Fed Chairman Powell utters the word “average” at the FOMC press conference. It matters what government officials do; not what they say.

The last time I saw people this confused was in 1981, when economists and investors were divided into two camps: those who believed rising budget and trade deficits would overwhelm savings and push interest rates higher, and those who believed tax cuts would trigger enough savings to swamp the twin deficits and drive rates down. As I argued at the time, that was muddled thinking on both counts. What mattered for interest rates was that the Fed had already undertaken actions that would destroy the return on the massive stock of tangible assets, which would change people’s minds about what they wanted to own.

Inflation matters just as much now as it did in 1981. It is the key to understanding the direction of bond yields, price-earnings multiples, EBITDA-multiples, and cap rates. And make no mistake, inflation is going up. A decade of firehose economics with the Fed printing their brains out, Congress helicoptering money on people’s heads, and silly ideas like Modern Monetary Theory flourishing in government mean inflation will surely be higher in the next decade than it was in the last decade. (Note: Any time you see an idea called “Modern” anything in economics you should raise your eyebrows.)

We have to think carefully about why inflation matters before we can know how to measure it. I will argue below that the CPI is the wrong way to measure it. For me, inflation matters because it makes people do things that erode the capital stock, and with it the long-term growth of output, incomes, and living standards. To see that, let’s get down to the most basic economics.

The Second Law

I have long believed that there is only one positive statement in all of economics; when people are presented with the opportunity to buy or sell the same good or service at two different prices they do the sensible thing—they buy low and sell high. It’s called the principle of arbitrage in the economics textbooks. Its implication is the Law of One Price; in an open market, there can only be one price for a given good or service. Never mind that later in the textbook the author defines a market as an area in which price tends to uniformity. #circular reasoning

Arbitrage is all there is in economics; the rest is just arithmetic. So, the next time someone gives you a complicated answer to an economics question and they can’t reduce their argument to someone engaging in arbitrage it is perfectly appropriate to blow the bullshit horn.

Arbitrage is a rebranding of the second law of thermodynamics, the bedrock of macroscopic physics. The second law states that in an open system differences in measures of state variables, like temperature or pressure, will tend to disappear over time as particles disperse. The same is true in economics.

So, how can we apply the concept of arbitrage to inflation and its ultimate impact on interest rates?

First Ask: Inflation of What?

The most important question we should ask is “inflation of what?” There are certainly thousands, if not millions, of prices in a modern economy to choose from. Every good, every service, and every input used to produce them has a separate price. Every asset and every liability has a separate price too. All of them can vary by location and over time. Which are the ones that matter?

If you are trying to figure out whether someone with a fixed-income can afford to buy groceries next year then consumer prices are the right thing to measure, although the official CPI is a terrible way to measure it. Housing costs make up 33% of the “market basket” of goods and services the BLS uses to calculate the CPI. Of that number, one fourth (7.7% of the total index) is rent paid by people living in rented accommodations—makes perfect sense. But three-fourths of housing costs, 24% of the total CPI, is a made-up number called “Owner-Equivalent Rent” (OER) that uses the rent paid by the people who do rent their homes as a stand-in for the cost of shelter for the much larger group of people who don’t rent their homes on the theory that it represents what people would have had to pay themselves to rent their own house.

Never mind that owner-occupied housing and rental housing are two completely different animals or that if an owner were to do so he/she would also have an additional income item that would exactly offset the imaginary rent payment. April OER over the previous 12 months was 2.0%; that means the rest of the index—the stuff with actual prices that people have to pay—was 4.9%, not the 4.2% in the press release. More about this bogus concept in a later post.

The CPI is also the right metric for guessing the total return on TIPS over the next 5 or ten years, not because it makes sense but because the piece of paper you own when you buy TIPS specifies that the inflation top-up used to determine your payment uses the official CPI to make the calculation.

But if you are interested in the long-term performance of the economy, measured by GDP, incomes, or living standards, the CPI is the wrong index. That’s because there is no way to define it as the driver of an arbitrage activity. The CPI market basket of goods is not suitable for measuring changes of value over time because most of it is comprised of services.

Here’s what I mean. Imagine an arbitrage experiment where both the one year Treasury yield and the CPI inflation rate are confidently expected to be 5% for the coming year, a situation most economists would describe as a zero real interest rate. The idea is that an investor should be indifferent to holding the Treasury or the basket of consumer goods over that year since both have a “return” of 5%, where the return on the Treasury is comprised of interest and the return on the market basket is the capital gain you would realize from its price increase.

But it doesn’t work that way. More than half of the value (59%) of the CPI market basket is made up of services—haircuts and guitar lessons—that disappear from your basket the moment you buy and consume them. Of the remaining 41%, 14% is food that will rot before the year is out, leaving just 27% in actual “goods” like cars, beer, and baseball hats that will still be there after one year. We can sum this up by saying that the physical depreciation rate of the things that make up the market basket used to measure the CPI is just too high for it to competitive with Treasuries in our arbitrage experiment.

What would make more sense would be an arbitrage experiment where we compare the one-year total return of holding a Treasury Note to the total return of owning a ton of copper, a gold coin, or a house because in each of those cases, the physical depreciation rate is so small that we can take the increase in its market price as a pretty good estimate of its capital gains yield.

Realizing this in the late 1970’s is what convinced me that the most important valuable for determining interest rates was not the CPI inflation rate; it was the inflation rate of the stock of long-lived tangible assets. If that’s true, then it must also be true that the right way to calculate the real interest rate is not to subtract CPI inflation from T-bill rates, it’s to subtract real asset inflation from T-bill rates. (You can download a paper applying the idea to Japan by clicking here.) When you look at real rates through the arbitrage lens, it gives you a whole different take on the economy.

For example, most people would say that February’s 0.08% one year Treasury yield and 1.7% 12 month CPI inflation implied a somewhat stimulative real rate of -1.62%. But the most recent (February) figure for the Case-Shiller Index reported home prices up by 12.0% from a year earlier, implying a hugely negative real interest rate of -11.9%, as shown in the graphic above implying monetary policy is aggressively stimulative.

Other measurement issues aside, this implies the owner of a house had a much higher return than the owner of a one-year Treasury over the year, high enough to convince investors to rebalance their portfolios to hold a smaller proportion in financial assets like Treasury bills and a larger proportion in houses and other tangible assets. It should come as no surprise to see that commodity prices are rising and bond prices falling (bond yields rising) in this situation.

So What?

The upshot of this is that the 231 economists in the opening paragraph got whiplash for nothing. Real asset inflation—the metric that really matters for the economy—is already here. It is certainly true that real asset inflation stimulates certain kinds of economic activity—ask the people at Home Depot.

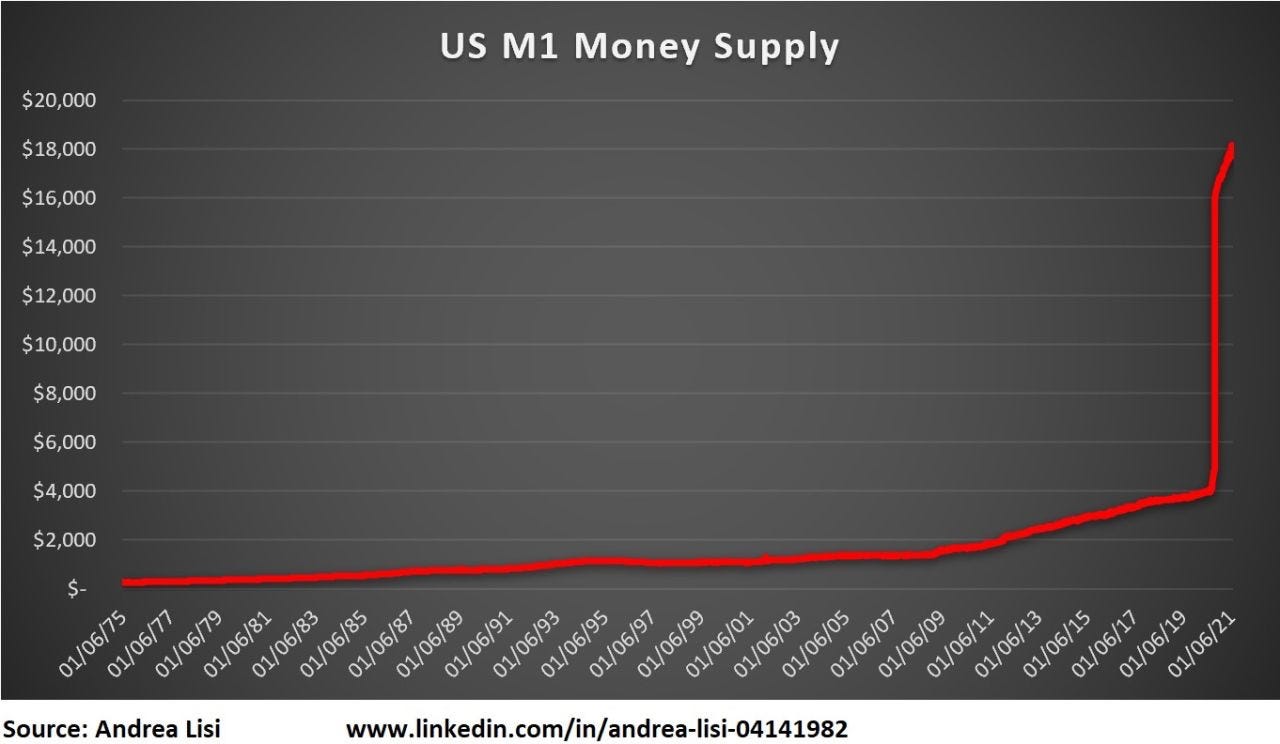

Helicopter money settling gently into people’s bank accounts stimulates economic activity too. The graphic above by Andrea Lisi, who writes good stuff, shows the money that government COVID-relief injected into people’s banks, pockets, and checking accounts). Asset price inflation also pumps up the net worth of the small fraction of people who live in the net worth economy relative to the large group of people who live in the paycheck economy, which really pisses them off and leads to all sorts of conflict and big tax hikes.

Most importantly, over the long-run, real asset inflation erodes capital formation by pushing investors into inflation hedges and tax shelters, as anyone who was awake and aware during the late-1970s can attest. It also increases the risk that we will wake up one morning surprised to see that the next credit crisis has already started, as we have done many times in the past.

I would welcome your thoughts on the topic.

Oh, don't get me started...first of all, you're wrong on the economists: there will be a positive impact on the economy because if they aren't producing their usual nonsense, people might actually think about what they are going to do instead of following what a talking head might say.

Second, measuring inflation is such an important thing that everyone does it wrong. Or, more exactly (and you touch on this), inflation is measured differently for different reasons: everyone can play the game and most do so to generate a number that has an agenda behind it. The CPI isn't an objective, dispassionate measurement: the government uses it to index how much pensions, etc. are going to increase, as well as a plethora of other uses, largely to avoid increasing outlays more than absolutely necessary. The CPI should be understood as the lower bound of general inflation: many price increases will be higher, and while some might be lower, they don't impact people the same way.

Any inflation rate that only looks at the standard , good x for price y on Thursday a month ago, what is that going to be this Thursday, ratio is going to find that a distorting influence will show up the farther you get away from that Thursday a month ago. Goods aren't constant: technology changes and the quality changes (hedonic deflators). I remember the first hedonic deflator for semiconductors: they started off measuring technical attributes per sq mm vs prices per unit, started off with the base year equal to 100 and called it off after three years because the index was 0.0000001 and falling. Technology had changed so much that they didn't have a useful basis for comparison because there was no useful basis for something changing that quickly.

Think of this way: interest rates are the price of money (what it costs to use it), inflation is the tax on money (what it costs not to use it). If the former is lower than the latter, sweet dreams for people lending; if the latter is higher than the former, the stuff of nightmares for the lenders. But none of that counts when the former is negative...because that means to meet revenue goals, there are no safe investments.