Tangible Assets

Wall Street has discovered real assets again. Maybe some day economics will too.

The same Wall Street guys that have been flogging the deflation story are now shamelessly posting articles about the inflation trade.

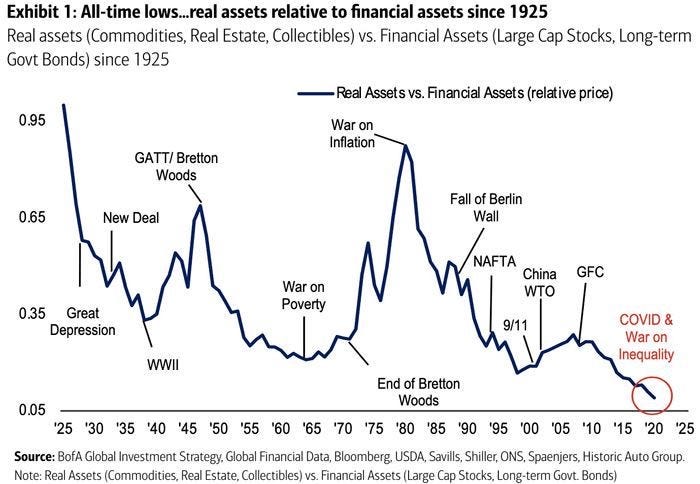

This chart from a BofA report I saw this week shows the history of the price of price of real assets relative to financial assets. While I might quibble with the details—their definitions of both real and financial assets are too narrow—their main point is correct. The relative price of real assets has fallen for the past 40 years but may be about to reverse course.

Tangible Assets and Interest Rates

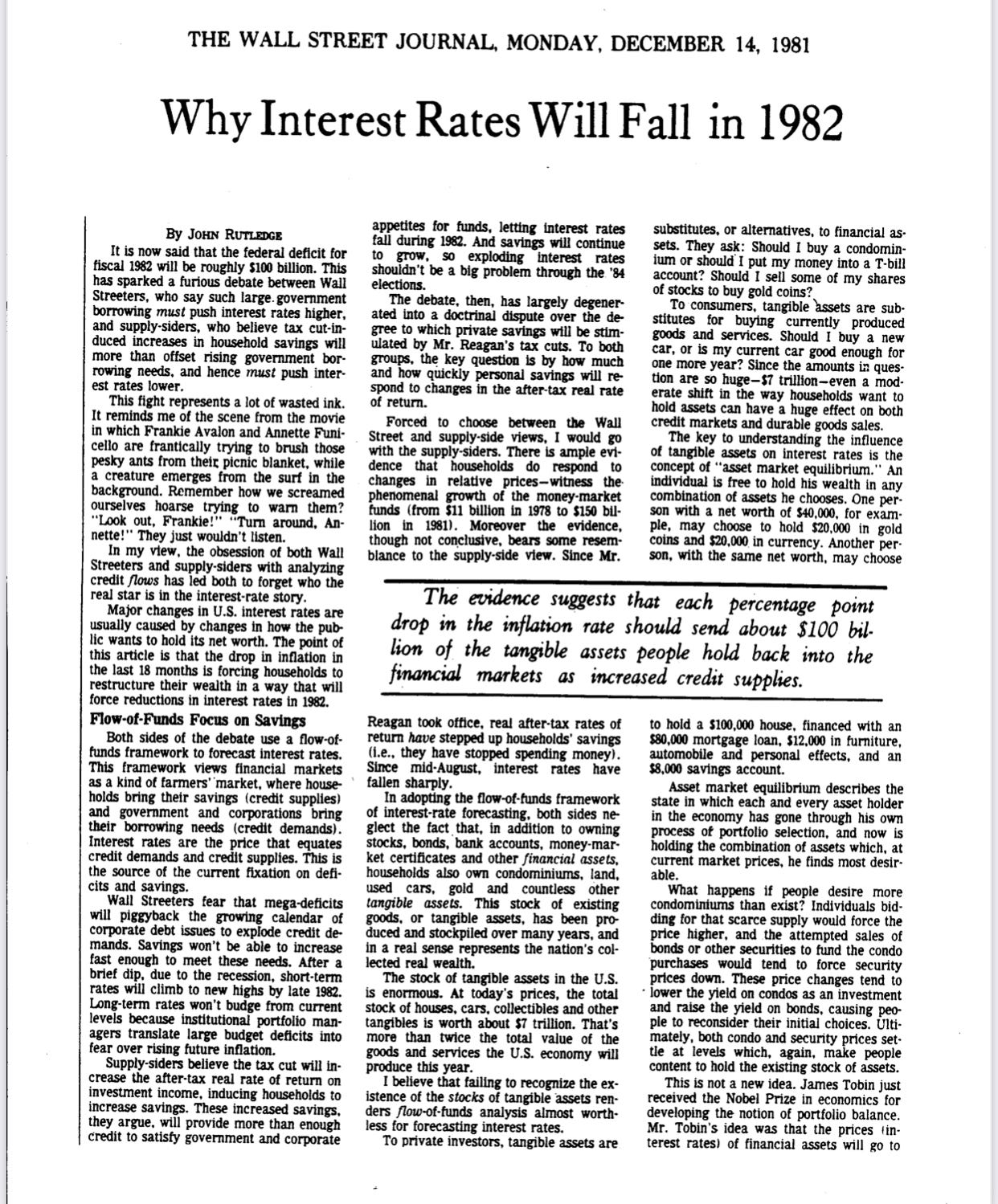

It has been almost 40 years since my name first showed up at the top of an article on the Wall Street Journal Op-Ed page. (Right at the point in the chart labelled “War on Inflation”). Once or twice a year since then some old guy (even older than me) stops me in an airport, pulls out his wallet, unfolds a yellow, crinkled piece of newsprint from the December 14, 1981 Wall Street Journal titled “Why Interest Rates Will Fall in 1982” and thanks me for convincing him to hang onto his Treasury bonds and collect 15% interest for thirty years.” I have posted a scan of the Op-Ed below in case you’re into ancient history.

To paint the picture in 1981, interest rates were very high (short rates above 20%; 30 year Treasury over 15%). Leading pundits were scaring people that rates would go even higher, because there wouldn’t be enough savings to pay for the Reagan tax cuts and rising trade deficit. I said no, interest rates would go down, no matter how big or small savings and deficits turned out to be. The gist of my argument was simple, as my ideas always are:

Dr. Doom and Mr. Gloom are using flawed logic. Interest rates are not determined by savings and deficits. They are determined by the price at which people are willing to hold the stock of existing assets .

People hold an enormous pile of assets on their balance sheets. Some are paper assets like stocks and bonds ($7.3 trillion at 1981 prices, about two years of GDP). Some are tangible assets like houses farms, and gold coins ($7 trillion) . All have yields made up of varying combinations of cash flow, service value, tax benefits, and capital gains.

People are not stupid. They respond to significant changes in relative yields by changing the allocation of the assets they want to own. (Thank you Prof. Tobin.)

The yield on financial assets is relatively simple to figure out. People collect interest, dividends, and capital gains. They pay taxes on all three at different rates. They like to collect interest, dividends, and capital gains. They don’t like to pay taxes.

The yield on tangible assets is a little trickier. Some of it is cash payments, like collecting rent on a rental property. Some is non cash, like the value of living in your own home. Some is capital gains (inflation). Some is taxed but there are also a slew of tax benefits (tax shelters) that accrue to tangible asset owners.

Volcker’s legacy of falling inflation and Reagan’s tax cuts both work in the same direction; they reduce the after-tax return on tangible assets and increase the after-tax return on financial assets.

The not-stupid people—see above—will decide they want a bigger slice of their portfolios in financial assets and a smaller slice (duh) in tangible assets.

People wanting to change their mix of financial and tangible assets doesn’t change the actual mix of assets at all since the assets already exist and have to be held by somebody. But it does change their relative prices, driving financial asset price up and tangible asset prices down.

What seems like a modest change in desired asset holdings is a huge dollar amount compared with the savings and deficits numbers people are worrying about. “…each percentage point drop in the inflation rate should send about $100 billion of the tangible assets people own (roughly 1.4%) back into the financial markets…”

Inflation in 1982 would likely be about 6%, compared with 10% the year before. That alone will increase demand for financial assets by $400-500 billion, driving stock and bond prices up and interest rates down. The Reagan tax cuts work will work in the same direction by decreasing the value of tax shelters.

“Interest rates must fall.”

The article drew a lot of unfriendly fire from both Wall Street and professional economists but my clients found it useful. I had developed the arguments during the late 1970’s when inflation, tax rates, tax shelters and interest rates were all on the rise. In the years after 1981, I used these ideas as the foundation for an asset-centric macroeconomic model I will describe in detail in later posts. Writing a book about it is on my Bucket List.

Fast Forward to 2021

So what does all this mean for today? Simple:

The Fed and other central banks are printing their brains out and promise they always will.

The government is spending gazillions of dollars on everything in sight. Budget deficits are huge and will stay huge.

To a first approximation, the only thing the Fed controls is its balance sheet and the only thing its actions determine is the price of the stock of tangible assets.

House prices and commodity prices are rising as a result. This, not the CPI, is the measure of inflation that matters for interest rates.

Bond yields will rise far above today’s levels. Multiples will fall.

I would rather own real estate than stocks or bonds while this is happening.

Dr. John

Excellent summary John, thank you! I particularly like the chart indicating the ridiculously low ratio of real vs financial assets. May I suggest that the unintended consequences for the myriad of policy responses to the pandemic actually resulted in a "war on equality."