Forget the Fed. Intrinsic Value, Intrinsic Risk.

Forget the Fed. Inflation, rates will surprise on the downside; spending, growth will surprise to the upside. Stock prices will reflect company performance, not Fed policy.

Summary:

Forget the Fed

Inflation, rates will surprise on the downside

Spending, growth will surprise to the upside

Stock prices will increasingly reflect company performance, not Fed policy

Investors need to understand Intrinsic Value and Intrinsic Risk

40 years of Fed-driven markets means investors have a lot of work to do

Groundhog Day

Friday morning, Punxsutawney Phil crawled out of his burrow for the 138th time, didn’t see his shadow, and announced there will be an early spring. That’s the good news. The bad news is that Punxsutawney Phil isn’t much of a forecaster. According to the NOAA, Phil’s track record since 1887 is just 36%.1 In the past 10 years, Phil saw his shadow seven times and was only right once, matching the Fed’s track record for forecasting their own decisions one year ahead in the FOMC dot-plot charts.

Forget the Fed

The good news for investors is that, after last week, we don’t have to waste all our energies trying to forecast what the Fed is going to do. Powell’s message was loud and clear. The Fed is going to be pushing the Fed funds rate down, not up, for the next two years. They are going to start as soon as, and continue as fast as, they are comfortable they won’t be embarrassed by a string of bad inflation reports. You can ignore the tricky questions from the child-journalists about the precise timing of the first cut (he doesn’t know) and the so-called neutral rate (he doesn’t know that either). Rates are going down from here. As investors, that’s all we need to know.

The precise glide path of rates will depend on the details in the inflation and employment reports along the way. The Fed has more confidence than I do in the quality of the data in those reports so don’t be surprised when they hyperventilate over every new data point. But we know enough about how the data is constructed to say that inflation will mostly surprise on the downside, which means rates are going lower, and jobs and growth will mostly surprise on the upside, which means the descent of rates is going to be slow.

The implication is that over the next two years, after more than 40 years of macro drama, stock prices will increasingly reflect company performance, as we saw with META and AMZN last week, and depend less and less on Fed policy. That means we need to focus on the Intrinsic Value of the companies we are investing in—their ability to generate a sustainable, growing, stream of free cash flow—and Intrinsic Risk—the political, economic, industry and company-specific events that can interrupt each company’s ability to produce free cash flow—when selecting what to hold in our portfolios. That’s a lot more work.

Here are a few thoughts on the economy, Intrinsic Value and Intrinsic Risk:

Why will inflation will surprise to the downside?

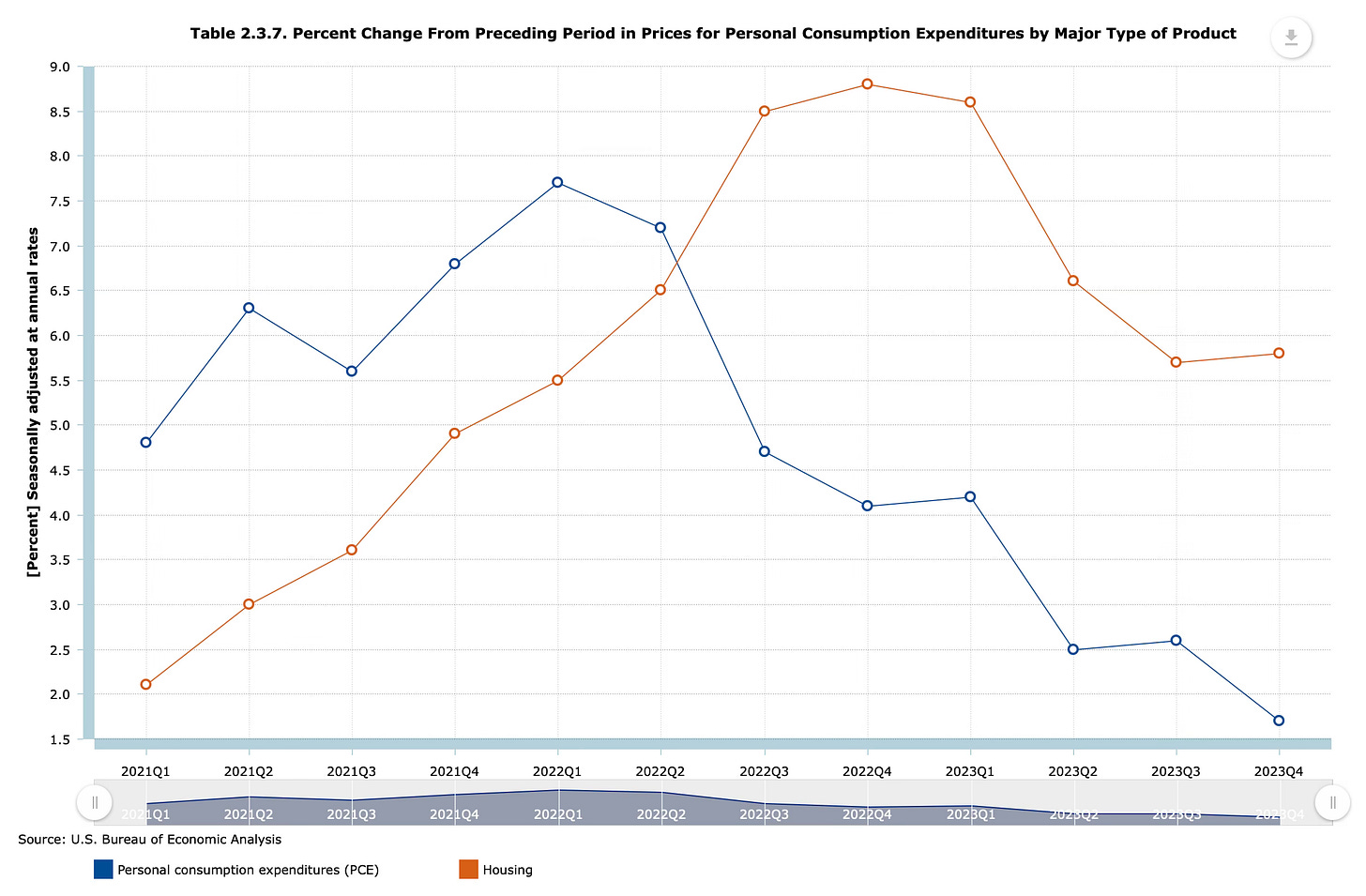

As we all know, the Fed’s pet inflation metrics are the 12 month rate of change in the PCE (Price Index for Personal Consumption Expenditures) and the Core PCE (PCE excluding food and energy.) In the December report, PCE came in at 2.6% and Core PCE at 2.9%, both lower than a year ago but both above the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Powell missed the chance to help the child-journalists understand why the numbers are still above target when he failed to tell them that both the CPI and the PCE currently overstate inflation because they include a made-up factor called Owners’ Equivalent Rent (OER)—the hypothetical amount a homeowner would have to pay to rent their own house from themselves (I’m not making this up!)—that effectively quadruples the weight of rent in constructing the indexes. (Note to reader: I hereby swear that I did not write a check to myself so I could live in my own house for the month of December.)

Including OER makes both the CPI and PCE higher than they should be, because rent has been rising faster than other costs over the past year as you can see in the chart above. Excluding OER (+5.8%) from the index, as I believe is appropriate, would reduce the PCE inflation rate for the 12 months ending in December from 2.6% to just 2.0%, hitting the Fed’s target.

For reference, the same calculation for last week’s December CPI report showed that removing OER (+6.3%) that makes up 26% of the index reduces the 12 month inflation rate from 3.4% (above the Fed’s target) to 1.8% (slightly below the Fed’s target.)

I’m quite sure that Powell doesn’t understand this because the Fed staff adamantly defends the OER abomination that has burrowed its way into the national income accounts, consumer income and expenditure reports, and the major price indexes. But he does understand that market rents on leases being signed today, as reported by Zillow and others, are at or below year ago levels. And he knows it will take more than a year for the collapse of rent inflation to be fully reflected in the data, which all but guarantees that reported PCE and CPI inflation will continue to decline for the rest of the year.

Why will growth surprise to the upside?

Recent data on Q4/GDP (+3.3% annual rate for the quarter) and January employment (nonfarm payrolls +350K jobs (double consensus estimates) plus +107K in revisions of previous months) were too strong to be consistent with private reports (ADP +107K jobs, and Challenger +82K layoffs for the month, most since 2009.) I am skeptical, both due to OER distortions (OER adds roughly $2 trillion per year to consumer incomes, consumer expenditures, and GDP figures, biasing levels, growth rates, and per capital income figures upward) and large seasonal adjustment factors that turned a unadjusted loss of -2.6 million jobs in January (from 158.3 million in December to 155.6 million in January) into a seasonally adjusted gain of 353K jobs for the press conference.

Don’t get me wrong; I don’t think that anyone fudged the numbers, just that seasonal adjustment can lead to nonsensical results after a 3 year pandemic. For what it’s worth, I trust the ADP report, which measures actual paychecks sent to actual people, more than the BLS figures that report what people told a guy they have never met on the phone when he asked if they were working last week.

The weak Household survey (-1.1 million jobs unadjusted, -32K seasonally adjusted) confirms my skepticism. The Household Survey commentary on page 2 used the phrase “little changed” nine times to describe the number of unemployed people, the labor force participation rate, the employment-population ratio, those working part-time for economic reasons, people not in the labor force who want a job, and those marginally attached to the labor force. I’m having a hard time getting from “little changed” to +353K new jobs for the month. So, color me as not convinced that the economy is as strong as recent numbers suggest.

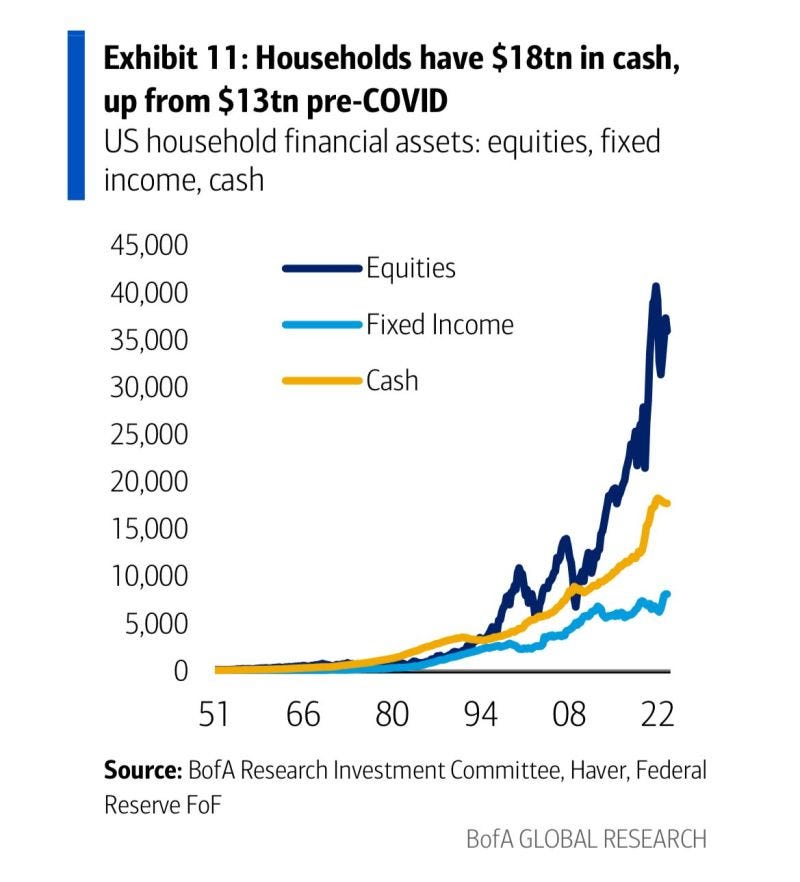

But I do believe the economy will continue to grow for one simple reason. As you can see in the chart, above, households currently have $18 trillion in cash and Money Market funds, up $5 trillion from pre-COVID levels.

If there is a law of gravity in economics, it’s “if you give people money, they will spend it.”

All this implies that the economic environment should be less turbulent than it has been in recent years, which implies that stock prices should be driven more by factors affecting the intrinsic values of the underlying businesses, and less by FOMC press conferences. That’s good news for investors willing to do the work it takes to understand the companies. Problem is, there are a lot of investors who have never had to do that work.

Intrinsic Value, Intrinsic risk

It may have been Yogi Berra who explained how to make money in the stock market. “First, buy a stock. When it goes up, you sell it. If it don’t go up, don’t buy it.” Yogi’s strategy worked pretty well over the past 43 years but I don’t think we can count on it going forward.

Markets since 1981 have been dominated by top-down forces—40 years of falling interest rates and rising multiples, the Subprime Debt Crisis, Quantitative Easing, COVID checks, and the Fed’s transitory inflation fiasco followed by big rate hikes. Darwin would expect that environment to have killed off most of the Ben Graham investors and put the top-down guys, who made all the money, in charge of Wall Street. And most investors are not old enough to remember anything else.

Some factoids: the average stock trader is 30 years old; the average Wall Street Journal subscriber is 47; the average S&P 500 company is less than 20 years old. (Here’s a sobering thought. That means the roughly 40 year duration of the average cash flow stream priced into the index is about double the average age (20) of the companies that are supposed to produce that cash flow run by managers who have been there even less than that.)

This is a great opportunity for bottom-up fundamental investors who understand that, in the absence of major inflation and interest rate events, you make all your money by investing in companies that generate sustainable, growing free cash flow and that the only time you get a high multiple is when you earn it by growing faster than your competitors. That means we need to focus on Intrinsic Value and its evil twin, Intrinsic Risk.

Intrinsic Value and Intrinsic Risk are big topics in themselves so I won’t try to deal with them here. Simply put, Intrinsic Value investing means separating and understanding the factors that are important for a company’s ability to produce a sustainable and growing stream of free cash flow—product development, customers, competitors, and management. Intrinsic Risk means understanding the most important things that can get in the way of those cash flows—disruptive technologies (AI, GLP-1), geopolitical events (Russia/Ukraine, China/Taiwan, U.S. tribal warfare), and failed business strategies.

Investment Strategy means developing a plan to profit from growing Intrinsic Value while protecting capital from the worst of Intrinsic Risk. The biggest risk today, of course, is the nonzero risk that global tribal conflicts spiral out of control. I will write about that in my next post.

Dr. John

Phil is aware that this is worse than flipping a coin but argues that fact is non-admissible because he does not have opposable thumbs he would need to flip a coin. He believes that same logic, however, does not apply to Chairman Powell.