Summary: Fed mistakes have brought the economy to edge of a credit crisis. Investors should be playing defense. Leave your emotions at the door. Don’t make major moves without long thought. Remain skeptical of incoming data. (I will write about a logical error in the CPI data tomorrow.) Hold too much cash—in Treasury bills, not your bank account.

Defensive Mode

As I wrote yesterday, when you find yourself dancing in the dark you need to slow down so you don’t knock something over. Instead, when Chairman Powell found himself in a situation we had never seen before, surrounded by bad data, he channeled his inner Paul Volcker and pushed interest rates too high too fast. The spike in rates triggered an avalanche of bank failures that has left the economy on the edge of a major credit crisis.

As investors, we can’t afford to make the same mistake. Here are a few things to think about before you make major changes in your portfolio.

Passion is not your friend.

We have all just been through a situation we never saw before that scared the heck out of us. Frightened people make bad decisions. Leave your emotions at the door. The right investor for today is the guy who would buy a sushi bar and rename it Restaurant for Cold, Dead Fish. If you can’t be that guy get someone else to do it.

At a recent dinner in Riyadh, a gentleman told me he likes my writing because there is no passion in it—I just help him think. I thanked him and told him that I had lived through so many financial crises in the last 50 years that the passion had been burned out of me. Now I make decisions slowly and carefully, especially during times of rapid change.

Beware of gurus and doomsayers, which means anyone who tells you how smart they were during the last crisis or who insists the world is going to end soon unless you buy what they are selling.

As a corollary, in today’s world, it is important that you not make real-time strategic decisions. Think through and decide your strategy in the calm, when the markets are closed; don’t change strategy or act on new ideas or new fears while you are sitting in front of the trading screen. If an idea is brilliant today, it will still be brilliant tomorrow after you have had a chance to sleep on it and discuss it with trusted friends.

Remain skeptical of incoming data

Today’s economic reports should have a warning label on the first page telling the reader to use the information at his/her own risk, to read all of the footnotes and to click through all the links in the report before reaching any conclusions.

Major life events like pandemics change people’s behavior in ways that will only become clear over time. Millions of people died; others are still grieving or sick with Long-COVID. Some have decided that a little more money isn’t worth it and have retired or otherwise left the labor force; some have gotten used to working in their sweat pants and don’t want to go back to the office.

It is unreasonable to expect data designed to measure normal times to capture these changes. Be especially skeptical of survey data collected by asking questions to frightened people during a time when response rates are falling, requiring the researchers who gather and process data to invent new “virtual” workarounds to fill in the blanks.

Don’t rely on seasonally adjusted numbers that purport to subtract “normal seasonal patterns” and so-called “outliers” before they show you the numbers. A pandemic is an outlier; and we don’t know what normal is yet.

Always look at unadjusted data first. This is a huge problem because the difference between adjusted and unadjusted data can be huge. Economic reports typically announce seasonally adjusted numbers. Journalists repeat them.

Some important economic reports—including the Producer Price Index, Advance Retail Sales, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization, ADP Employment Report—don’t bother to show you unadjusted numbers at all. Make sure you click through the links in the footnotes until you find where they are buried before you reach an opinion about the report.

Hold too much cash—in Treasury bills, not in the bank.

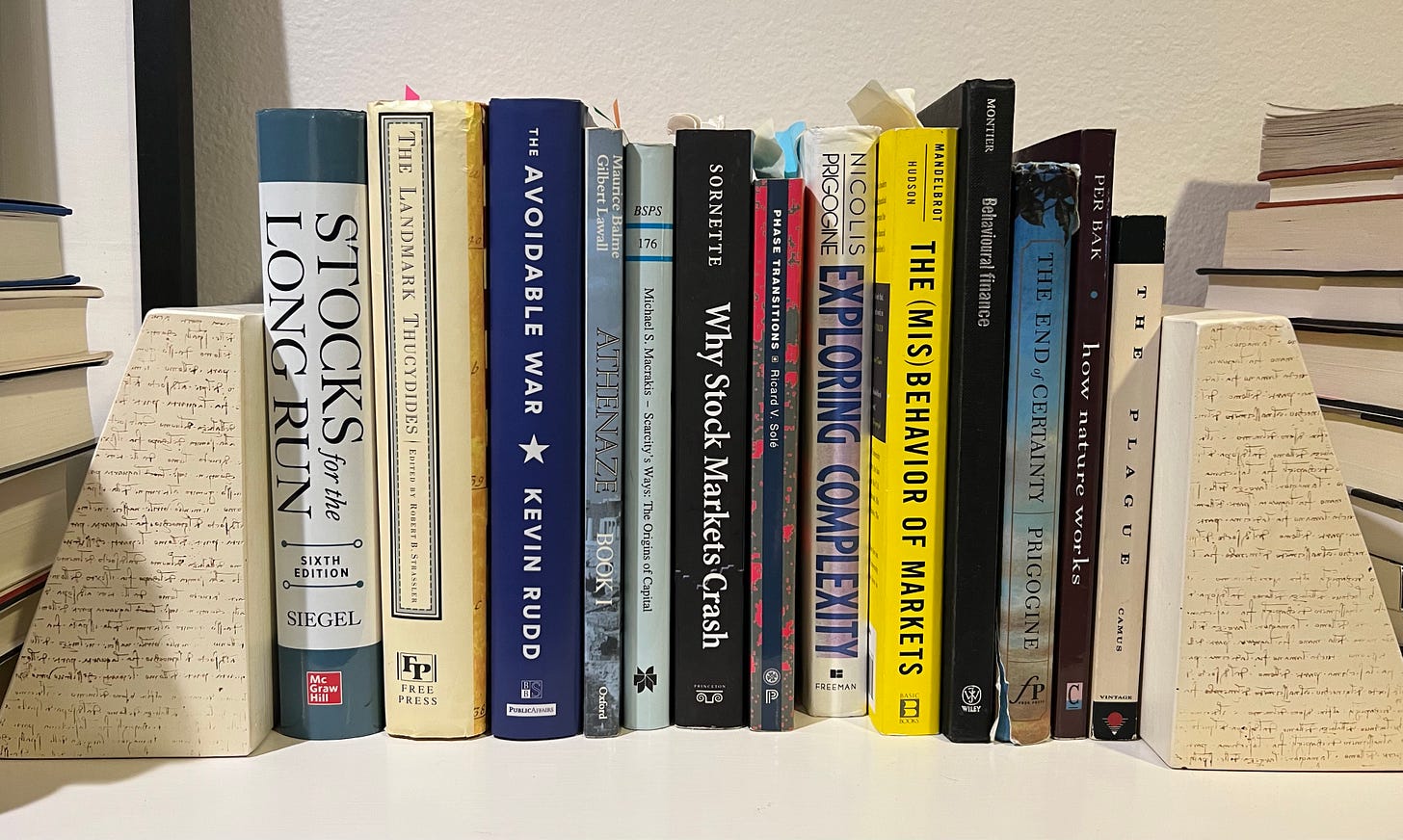

Investors all have the same fundamental problem, whether to be in or out of the market. On one end of my bookshelf is Jeremy Siegel’s Stocks for the Long Run, that convincingly shows owning stocks is the best long run strategy for making money, i.e., that not owning stocks is a risky strategy. (Disclosure: Jeremy is an old and treasured friend—we sat next to each other as graduate students in Milton Friedman’s Money Workshop a half century ago.)

On the other end of my bookshelf are books by Bak, Prigogine, Montier, and Barabasi showing that the economy and financial markets are far-from-equilibrium complex systems that periodically experience the cascading network failures we call recessions, depressions, credit crises and financial panics. You can read more on credit crises, cascading network failures, and investment strategy by clicking here.

The world we live in, of course, lies between those two bookends. My way of handling the uncertainty is to build a portfolio of Greatest Companies in the World stocks—you know the names as well as I do—and to stay fully invested in them most of the time. I say most of the time because when it has been snowing so long that the mountain is starting to sag I shift a hunk of the portfolio to Treasury bills so, in the event there is an avalanche, I have plenty of cash to buy stocks at half price. I don’t make this change very often and never without plenty of thought.

I am holding 40% of my personal portfolio in T-bills today. This is a good time to be extra careful.