Dancing in the Dark

The Fed Can't Make Good Decisions with Bad Data. Neither Can Investors.

Warning: If you came here looking for a complete, logical explanation for the state of the global economy, financial markets, and geopolitics just walk on by because I don’t have one. In my 50 years as an economist I have never seen a more complicated situation. Confused or not, though, we still have to do our jobs as investors to protect and, to the extent possible, grow the value of the capital in our care. Here are a few thoughts on how to do that until things settle down. I welcome your comments and ideas in return.

Fed Policy—Too Far, Too Fast

May 8, 2023. The Fed made the mistake of raising interest rates another quarter percent last week, likely ending the most aggressive series of rate hikes since Volcker’s Saturday Night Massacre in 1979–when 3 of the current FOMC voting members weren’t old enough to go to middle school yet.

If I were a board member I would have voted against the increase. Not because 5% is too high, but because, as both Bing Crosby and Bruce Springsteen warned, when you are dancing in the dark you need to be careful or you’ll knock something over. When you find yourself in a situation you don’t understand and you don’t trust the data you rely on to make decisions, humility, not hubris, is the way to go.

Too late now. The Fed knocked over another bank last week when the FDIC told Jamie Diamond he could now kiss another bride—this time First Republic Bank. Judging by the collapse of regional bank share prices later in the week, it won’t be the last bank to fail.

People are sifting through the rubble of the three recent bank failures—Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, and First Republic Bank—looking for what special factor caused each one of them to fail. But it makes no more sense to ask what made depositors pull their money out of a particular bank than it does to ask which snowflake started an avalanche. As physicist Per Bak explained, catastrophic events, like avalanches, earthquakes, mass extinctions (or, indeed, bank failures) “can occur for no reason whatsoever ... without any external triggering mechanism.” Once enough snow has fallen on a mountain to bring it to a self-organized critical state any number of snowflakes are poised to trigger avalanches of all sizes.

In this case, the Fed drove the banking system to a critical state over the past decade by pursuing a string of quantitative easing (QE) programs that drove asset prices ever higher and convinced investors they were geniuses, followed by the COVID pandemic that triggered more QE and a ton of helicopter money that piled up in people’s checking accounts begging to be spent. When COVID forced factories to close and shut down ports across the world, those obese checking accounts and acute supply shortages drove prices sky-high. Analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco suggests that both supply and demand factors were at work, as you can see in the chart below.

Ignoring Bruce Springsteen’s wise counsel, the Fed slammed hard on the breaks, hiking short term interest rates by 5 percentage points in just over a year. The spike in rates drove down the market value of stocks, bonds, and real estate loans on bank balance sheets, and undermined the value of the collateral they hold as security against loans. Big depositors eventually saw through the regulatory sleight-of-hand—accounting rules that allowed banks to report the value of underwater bonds as if they were still worth what they paid for them—and pulled their uninsured deposits out of the banks.

As everyone knows, runs on banks can lead to credit crises that can shut the place down. Not the incremental tightening of lending standards that Powell told us is like another quarter point bump in the Fed funds rate. In a real credit crisis, like the ones we experienced in 2001 and 2008—known as cascading network failures—the links connecting lenders and borrowers fail and credit markets switch into a state of non-price rationing, where the effective cost of capital is many times higher than the rates you read in the newspaper.

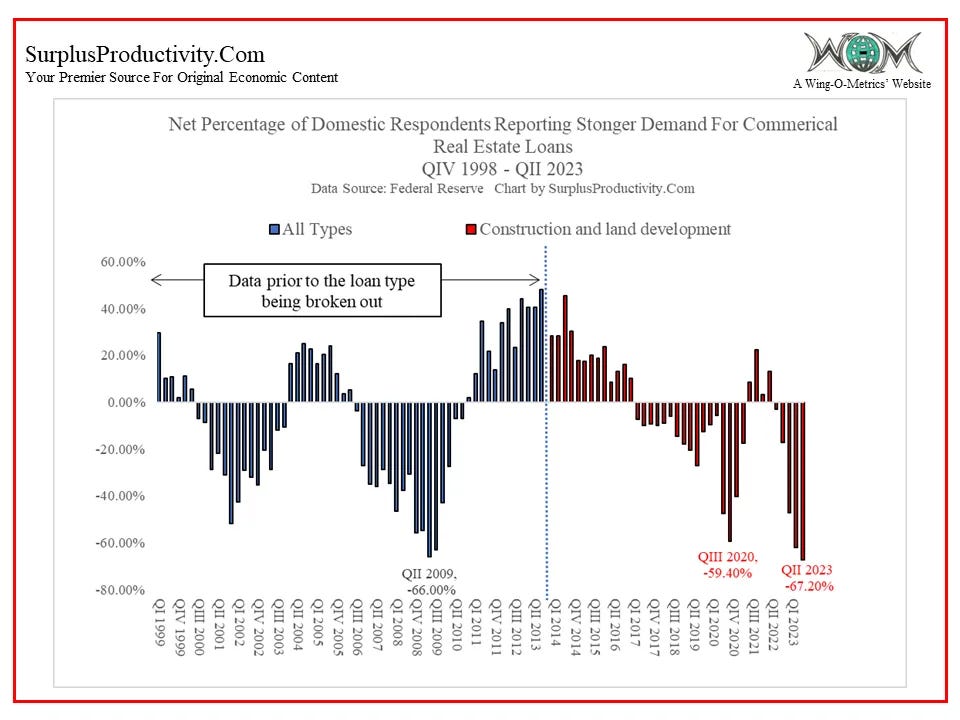

We are not in a full-blown credit crisis yet but there is a decent chance we will get one. Some corners of the capital market, e.g., CMBS refinancing, are effectively closed for business. And, as you can see in the chart, above, today’s Senior Loan Officers Opinion Survey (SLOOS) shows that banks have already significantly tightened lending standards. As Barry Knapp points out, although the SLOOS report was released today, survey responses were due on April 7, more than a month ago. It’s a good guess that credit standards have tightened a great deal more since then.

The SLOOS report also shows that commercial real estate loans are the eye of the credit hurricane, as Paul Wingart pointed out today. Interestingly, when banks shut off credit, they typically report the drop in lending as a decline in loan demand. I learned that the hard way in 2001 when I wrote an Op-Ed for the Wall Street Journal (sorry, can’t find the link) pointing out the role of credit rationing in the Dotcom crisis; triggering nasty Letters to the WSJ Editors from both the Comptroller of the currency and the head of the Bankers Association saying I was dead wrong and that borrowers just no longer wanted their money.

We are not in a crunch yet. The most recent Fed weekly H8 report shows that, as of last week, banks were still making business and consumer loans. But that can change in a New York minute.

Investors need to be in defense mode before that happens. That means stay calm, remain skeptical of incoming data, and hold too much cash—in Treasury bills, not in the bank. I will write more about these ideas in tomorrow’s post on how to protect your portfolio from bad data.

this time John, you are NOT dead wrong. and, of course, as we've discussed, beware the data. swk

commenting on john rutledge’s excellent article on cpi overstating inflation. it’s even worse than he notes (and not because data providers are letting us down, but because in an industrial revolution with dramatic increases in new products and product quality, it'‘s very, very hard to accurately measure cpi changes). prices adjusted for both john’s points and product quality are rising much slower than published cpi suggests. great job, dr.john!