Ricardo and the Gains from Trade in Graphs

March 29, 2020. Ricardo didn't write what most economists think he did.

Note: Warning! This post is going to be particularly nerdy—about halfway between Mr. Wizard and your first economics professor. But is you have a propeller on your head read on.

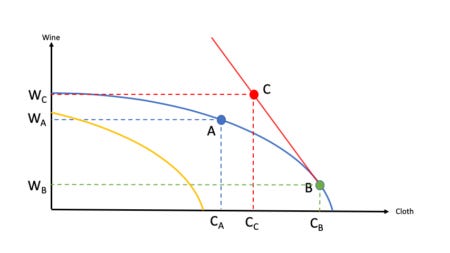

Before trade, in the above graph, England chooses to produce and consume at point A on its Production Possibility Curve. With trade, England can shift production to point B and consume at Point C by selling cloth for wine according to the terms of trade (relative price) indicated by the slope of the red line.

The graph above shows free trade equilibrium, where England exports X=CB-CC cloth and Imports M=WC-WB Wine and consumes the combination of wine and cloth at Point C. Point C is above and to the right of the pre-trade Production Possibility Curve, therefore unobtainable in the absence of trade.

Both of the above graphs assume, like Ricardo, that capital cannot move between countries. If capital can be redeployed to seek its highest return, the whole story changes. In this case, we assume that England is more capital-rich than Portugal, i.e., returns are higher in Portugal. Under these conditions, owners of capital will redeploy it from England to Portugal. With less capital, England's Production Possibility Curve shifts left to the yellow curve, from which none of the points A, B, or C can be reached.

It is important to note that the last graph showing free-trade equilibrium with mobile capital no longer allows us to make statements about the level of economic welfare in England. That's because, in addition to collecting their share of output produced in England (which is larger because the return on capital is not higher) the owners of capital are now also collecting returns on the capital they have deployed to Portugal.

We can, however, say that English owners of capital are better off and English workers are worse off that before trade. That's because English capital owners and English workers no longer share the same fate. In a very real sense, trade has changed the definition and composition of the British nation.

I think this is a pretty good representation to what has happened in the US, Europe, Japan, and other rich countries in recent decades. And the flip side is a pretty good description of China, India, and other low-income countries. It explains why workers are so angry in some places and not others, and the rise of populism in rich countries. Try as they might, I don't think that governments are going to have any success stopping these changes. This has profound implications for investors in the coming years.

Dr. John