Part 2 of 2: COVID and Cities. Investment Strategy

Understanding the economy as a complex system operating far from equilibrium, prone to the periods of sudden, dramatic collapse that we know as financial crises.

Note to subscribers: In my last post, I posted the first half of a longer paper on the impact of COVID-19 on urban real estate. This post is the second half of the full paper outlining an economic model and investment strategy for the post-pandemic period. You can download a PDF file of the full paper, including all of the references, by clicking here.

Summary: They’ll Be Back

In the first half of the paper, I focused on a single question: will cities ever be able to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic? I presented evidence that cities have, indeed, been hit hard by the pandemic. I reviewed three different bodies of evidence—1) the historical record of cities and pandemics, 2) the economics literature on agglomeration, and 3) the scientific literature on scaling laws in complex systems. I concluded:

There is a reason--superlinearity--why cities like New York were hit harder than suburban or rural areas others during the pandemic.

That same reason will make people return to the cities once the pandemic is behind us, just as they have done for thousands of years. With apologies to Arnold, they’ll be back.

Historically relatively successful cities, like New York and the San Francisco Bay area, where local factors have made them outperform expected levels, will recover faster than other, historically less successful cities. Estimates show that outperforming cities will continue to be more successful than other cities for many decades into the future.

The implication for investors is clear. As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, investors will be rewarded for focusing on urban property, not suburban or rural property, and they should focus on top quality assets in historically successful cities like New York and San Francisco, not chase apparent bargains in smaller, less historically successful areas.

Implications for Investors

In the remainder of this paper, I want to focus on a broader topic: how these conclusions fit into an overall investment strategy. That requires us to consider three issues:

the appropriate overall role of real estate in asset allocation,

which sub-sectors of real estate to focus on, and

the most complicated issue of all, when is the right time to make the investment.

Answers to these questions must be made in the context of an analytical framework capable of explaining the periods of growth punctuated by collapses into economic and financial crisis once or twice each decade that characterize developed economies like ours. I will describe such a framework below.

For reasons explained in depth in a separate article (Rutledge, 2021), accepted macroeconomic models of the sort taught in many PhD programs and used by the Fed and other central banks are disappointing in this regard. Their myopic fixation on explaining output and employment—the economy’s profit and loss statement—makes them unable to explain the much larger events taking place in asset markets—the economy’s balance sheet. And their worship of so-called micro-foundations has led them to characterize the economy as being in general equilibrium at all times, only being nudged away by temporary, gentle, normally distributed exogenous shocks. The end product has been elegant models that do a poor job explaining the real world. For that reason, I have spent much of the past four decades developing an alternative framework designed to embrace asset market shocks and financial crises as normal events. The following section is a brief summary of the logic behind our approach and how to apply it to the post COVID-19 economy and markets.

Far from Equilibrium Economics, Storm Systems and Weather Map Investing

The analytical framework behind our investment strategy differs from standard macroeconomic models in two important ways.

First, it is asset-centric in the sense that it acknowledges that our economy asset markets are many times bigger and more influential than are GDP accounts. Disturbances in our $400 trillion balance sheet have much more dramatic effects on people’s lives than disturbances in our $20 trillion GDP accounts. To a first approximation, all economic crises arise in the asset markets. We even name our crises after asset market events like the savings and loan Crisis, the dotcom crisis, and the subprime debt crisis. My work on this issue started during the inflation of the late 1970s and was first published in a series of articles in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and Financial Times in the early 1980s (Rutledge, 1981, 1982a, 1982b, 1982c, 1983, 1984, 1985a, 1985b, 1986a, 1986b, 1986c). I have used this framework to advise pension funds corporations, and policy makers and to make investment decisions for more than four decades.

Second, our analytical framework is designed to represent an economy not as a flow of goods and services in static general equilibrium but as a complex adaptive system, operating far from equilibrium, and prone to the periods of sudden, dramatic collapse that a physicist would call phase transitions and we know as financial crises (Solé, 2011; Sornette, 2003). I have outlined the logic of that approach in a recent journal article (Rutledge, 2015).

My interest in financial crises grew out of my early days as a private equity investor where I learned two painful lessons: 1) financial markets are not always in price-clearing equilibrium as promised by the textbooks and 2) the cost of capital during the periods of nonprice credit rationing that always accompany financial crises is much, much higher than the interest rates posted in the newspaper.

As a personal aside, I was introduced to complex adaptive systems, network theory, criticality, and far-from-equilibrium physics dates in the early 1990s by my (brilliant) daughter Jessica one weekend in 1994 when she came home for the weekend with friends from college. Jessica was an economics major at Williams but found the economists too boring (told you she was brilliant) so she lived in the math dorm with more interesting friends. I was puzzled by an experience I had recently observed in my private equity practice where I had witnessed credit markets close down like a snapping turtle, which is not supposed to happen in economics. She and her friends told me about an exciting new idea called “Complex Adaptive Systems”, they had learned about from one of the math professors. We stayed up all night talking about it. I read everything I could find on it, which wasn’t much—remember, no Internet—and started looking for more. I mentioned my interest to Shortly my friend and client Bill Miller at Legg Mason, who told me he was Vice Chairman of the Santa Fe Institute where the serious work on complex systems was taking place. Bill gave me a copy of Linked (2002), Barabasi’s book on network theory. My brain has not been the same since. After writing and lecturing on the topic for many years, I developed a course in far-from-equilibrium economics and finance that I taught for many years to the PhD students at the Claremont Graduate University (Rutledge, 2020).

In our framework, a financial crisis is a phase transition from a state of general equilibrium to a failed-network state caused by a sudden collapse of financial markets known as a cascading network failure (Barabasi, 2002). You can think of a phase transition as an avalanche, earthquake, tsunami, or hurricane, each of which is an energy transformation that produces sudden, violent change (Bak, 1996). Understanding the nature and timing of these phase transitions between periods of more-or-less general equilibrium and periods of capital market breakdown is the essence of understanding financial crises. It is also the essence of designing an investment strategy.

The Four Stages of a Financial Crisis

I think of an economy experiencing a financial crisis as traveling through four stages. In the first stage, the economy is in a state of full employment that economists call general equilibrium. In the second stage the financial markets suffer a brief but violent collapse. In the third stage, credit markets are effectively closed for business and the economy limps along in recession. In the fourth stage, financial networks regrow lost connections and the economy grows back toward full employment, after which the round trip is complete and we find ourselves again in stage 1 at full employment.

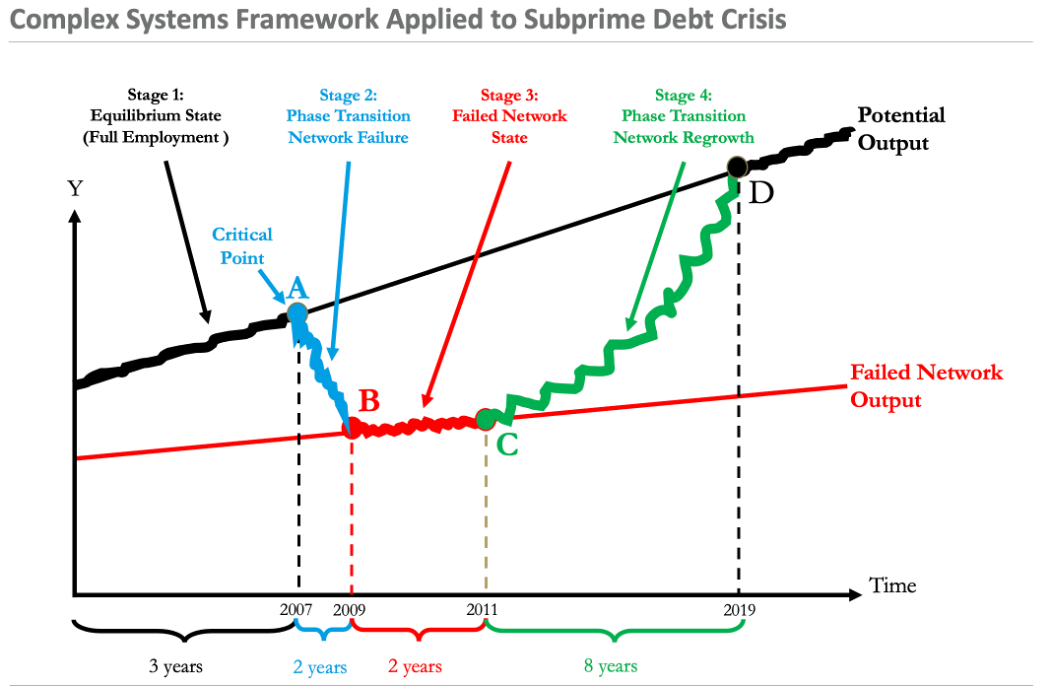

Figure 9 above applies this analytical framework to the subprime debt crisis as an example of how an investor should think through the investment timing decision in a world where financial crises are regular events. You can find a more thorough description of our analytical framework in a separate article (Rutledge, 2021).

There is a lot of information piled into Figure 8 so I will build it up layer by layer to give you a mental model for thinking about financial crises in a complex systems model. The first layer is that we will distinguish between two very different states of the economy. But first I want to explain what I mean when I use the word “state”. The concept of multiples states is unusual in economics but very common in the physical sciences where there is a long tradition of studying the dynamics of systems. The most familiar example to most people is states of matter. We all know that water and ice are simply two different physical states of a system of H2O molecules. Both are made up of the same basic units; what’s different is the rules of engagement among the units, how they interact with one another. In the liquid state they are far enough apart that they can move; in the solid state they are locked into an unmoving structure. As a researcher, which state I want to consider will be determined by what question I want to ask.

As a second example, imagine that you are landing at LAX at midnight after a long flight from Maui and you want to get home and climb in your bed in Newport Beach. How long will it take to get home? I use this to explain multiple states to my students—it is a true story. If you consult Google Maps for the best route, it will tell you that the distance is 48 miles and that it will take you 48 minutes to get there. In my case, it took two and a half hours (with a one-year-old in the back seat). What went wrong? The problem was simple.

Google assumed that the transportation system was in its normal state and knew that the best route was to take the freeway. Unfortunately, Google didn’t know that the system was in an alternative state; the freeway had just closed for repairs so I would have to take surface streets all the way home.

When analyzing the behavior of systems there are always assumed underlying states to consider. For the highway story it is the difference between the state of the transportation system when everything is working and the state where part of it is shut down. For economies it is the difference between the state of the economy when the financial system is working and the state where part of it is shut down. In both cases the underlying cause of the second, less efficient, state is a network failure that reduces the system’s throughput. I describe the two states relevant to financial crises more fully below.

State 1, represented by the black line labelled “Potential Output”, shows what the path of output would be if the economy were able to remain in a state of general equilibrium at all times. We can think of the black line as potential output, as full employment output, or as general equilibrium from the textbooks. In general equilibrium, a market economy is extremely efficient. Market prices are doing their job of reliably transmitting information on wants and scarcities along the communications network we call the market to the people who need the information so they can make decisions, as described by Hayek (1945) in his classic article. If nothing ever went wrong with the information network, this would represent the growth of the economy over time.

State 2, represented by the red line labelled “Failed Network Output”, tells us what the output of the economy would be over time if financial markets never worked properly. By not working properly, I mean just the opposite of Hayek’s smoothly functioning markets; a situation where people do not trust the information signals (prices) they receive from the economy’s financial markets. The resulting cascading network failure interrupts the functioning of financial markets just like what happens when a power grid goes down during a thunderstorm. The lights go out until the network has been restored.

Now let’s walk through the timeline of a financial crisis from beginning to end. We will divide the timeline into four stages, each representing a different state of the economy and markets.

Stage 1, the heavy black segment to the left of point A in Figure 8, is where our story starts. It is 2007. The economy is crawling up the black line from left to right, operating at full employment, or general equilibrium, having fully recovered from the 2001 dotcom crisis. The economy was strong in 2007: growing output and employment, rising profits and valuations, and a housing boom facilitated by the rapid growth of fancy new securitized mortgage products that everybody loved but nobody understood. Sure, home prices had just started to fall but there was little reason to worry; financial markets were so efficient there wouldn’t be more than a speedbump. We had no idea there was another financial crisis just around the corner. Unfortunately, as pointed out by Minsky (1992), good times breed excessive optimism, weakening credit discipline, and overborrowing, ending in what is now referred to as a “Minsky Moment” when liquidity disappears and financial markets freeze up. That moment is Point A on Figure 8. You can think of it as Saturday when the news cameras showed Lehman employees leaving the building carrying cardboard boxes.

Stage 2, the heavy blue segment between points A and B, is the crisis phase. It represents the air pocket, or phase transition, when the economy switches from a state of general equilibrium to one characterized by failed networks accompanied by the sudden, violent meltdown of financial markets. Like violent storms in nature, the crisis phase is destructive but short-lived. It puts tremendous pressure on overleveraged investors, turning them into forced sellers, and creates extraordinary opportunities for unleveraged investors with positive cash flow and plenty of cash.

Stage 3,the heavyred segment between points B and C,represents the bottom of the recession, the clean-up period after the crash when unprepared investors struggle to make debt and interest payments and lenders force refinancing and fire sales of quality assets. Stage 3 is a time of extraordinary distressed-credit opportunities.

Stage 4, the heavy green segment between points C and D, is the longer period following the recession when financial markets are becoming more accommodating to borrowers and the economy slowly grows back toward full employment. This is the time of major improvements in profitability and performance, easing credit standards, and rising valuations. It ends when the economy has once again reached full employment and valuations have recovered to normal levels, starting the whole process again.

Asset Allocation, Market Timing Issues

Not surprisingly each stage of this process has its own return profile and its own best investment strategy. Using the dates shown in Figure 8 from our analysis of the subprime debt crisis, the cumulative returns for various asset classes during each of the four stages are shown in Figure 10 below.

Stage 1 Returns. Not surprisingly, all asset classes show positive returns during Stage 1, the full employment period that precedes a financial crisis. But the returns are modest for fixed income investments and comparable for most equity asset classes, perhaps reflecting strong operating performance in a growing economy that has already been capitalized into asset prices and financial markets doing their job arbitraging away abnormal returns.

This is the time when an astute investor reduces leverage, harvests fully valued assets, and builds cash. This is easier said than done. At this point investor have made a lot of money for a long time; every bone in their body is screaming to stay invested.

Stage 2 Returns. Returns on risk assets are uniformly negative during Stage 2, the crash section of the financial crisis. Only cash and bonds show positive returns, driven by aggressive interest rate cuts by the Fed during the crash.

For investors who raised cash during Stage 1, this is a time for patience. For those investors who missed the opportunity to raise cash during Stage 1, it is too late to sell.

Stage 3 Returns. The period after the crash is an extraordinary time to be an investor. Bonds show good returns, equities even better, but the big money is made in real estate. Investors who have bought top quality assets at discount prices show ext5raordinary gains, even during a recession.

This is a time to (carefully) deploy cash into special situations created by the crisis. During Stage 3, commercial real estate investments far outperform other asset classes.

Stage 4 Returns. Stage 4 is every investor’s dream. Investors make money in two different ways. First, both businesses and real estate assets show improving operating performance driven by strong economic growth as the economy works its way back toward full employment. Second, financial markets are beginning to function more efficiently again, which means easier credit availability and rising valuations. With rising cash flows and rising valuations investment returns are extraordinary, with cumulative returns in Hospitality (322%), Industrial (272%), and Multifamily (173%) on top of the impressive returns they have already earned in Stage 3.

This is a time to be fully invested in prime real estate assets, to invest in their growth, and to prepare for the harvest stage that will arrive again once the economy has reached general equilibrium.

Taking Stage 3 and Stage 4 together, real estate investments acquired early in Phase 3 after the meltdown, and sold at the end of Stage 4 when the economy had reached full employment again were worth 8.9x the initial investment, ranging from 6.6x for Office, 7.9x for Multifamily, 10.7x for Industrial, and 15x for Hospitality.

For these reasons, we believe the most interesting opportunities after the COVID-19 pandemic will be in real estate, not in the stock market. Both the likelihood of higher inflation and the near certainty of higher tax rates will drive investors to restructure portfolios away from long-duration financial assets, like equities and bonds, and towards property and other real assets. This will result in substantial capital gains for real asset owners.

Within real estate, we believe there will be especially attractive opportunities in three areas:

Multifamily. Operating performance will improve significantly when young people move back to the city. Cost of capital will decline sharply once financial markets are functioning properly again.

Hospitality. We expect to see exceptional opportunities to buy hospitality assets at deep discounts driven by the financial distress of current owners and weak operating performance during the COVID-19 lockdown. When cities are back in business again, the hotels will be full again.

Office. Distressed owners and pessimism over the future of the office will create opportunities to buy offices in the best locations at discount prices over the next two years. Although there may be changes in the demographics of who is showing up for work in offices, financial, professional, and creative businesses are going to expect their employees to show up for work again.

The key is timing.

We have not seen the COVID-19 financial crisis yet. Financial markets began to seize up last March—at one point there were no bids for Treasury bonds—forcing the Fed to engineer massive purchases of assets and the Federal government to unleashed two trillion dollars of fiscal stimulus with the CARES Act. These policy interventions stopped the financial market meltdown and temporarily supported the economy. Household disposable income during March-December of last year was roughly 10% higher than it had been a year earlier, even though ten million people lost their jobs and millions more were unable to work. A second, smaller, stimulus package in December included $600 stimulus checks; as a result, government checks made up more than 30% of household income in January. Next month, when the $1400 checks from the Biden stimulus package are mailed, people will be awash in cash again. But the stimulus checks can’t go on forever.

The stimulus measures delayed the beginning of credit crisis but did not prevent it. When the stimulus ends later this year, as it surely will, asset owners will find themselves with more debt and less cash flow than was true before the pandemic began. People will have to make mortgage, credit card, and student loan payments again. Lenders will again be able to enforce loan agreements and seize assets in delinquency. The result will be tightening credit and forced asset sales, which will create exceptional opportunities to deploy capital in the second half of 2021 and all of 2022.

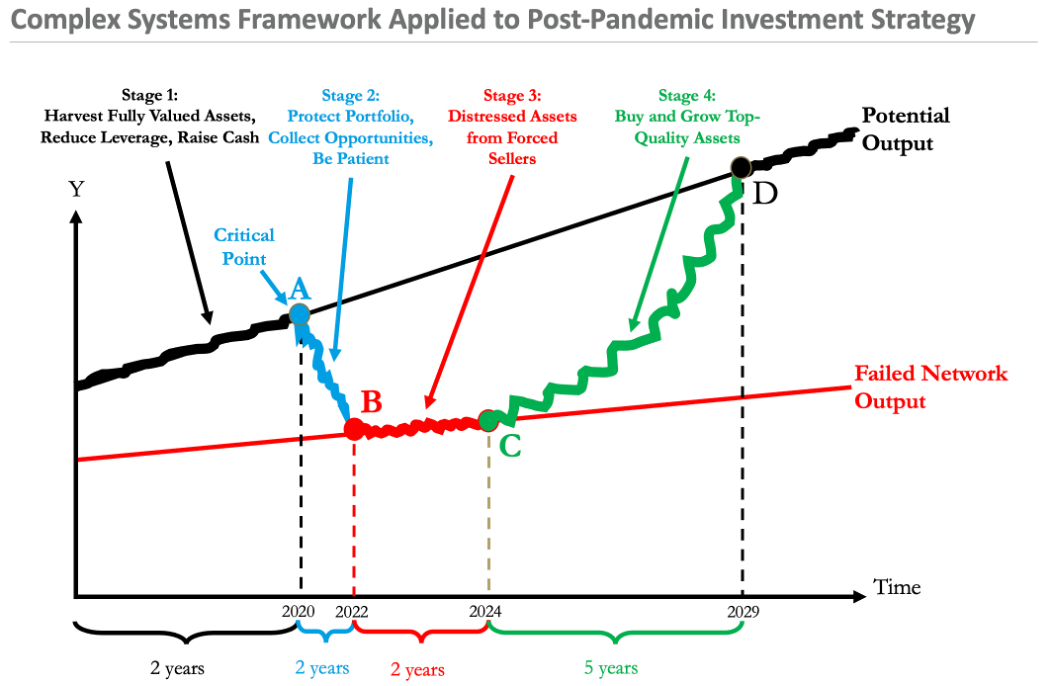

Figure 11, above, paints a picture of how the four stages of the post COVID-19 economy are likely to play out. In constructing the illustration in Figure 10, I have used the data from the Subprime Debt Crisis to mark the endpoints of the four stages of the credit cycle, showing two years for Stage 2 and two years for Stage 3. I assumed 5 years to illustrate the period of recovery and network regrowth in Stage 4. That’s somewhat shorter than the 8 year Stage 4 period in Figure 8 for the Subprime Debt Crisis but there is no clear case to prefer one over the other. We know that the stage 4 network regrowth process will take much longer than the Stage 2 meltdown but there is no way to make a precise estimate of when we will reach full employment output again.

In summary, the massive government stimulus provided by Congress and the Fed have delayed the onset of the financial crisis but have not prevented it. I expect tightened credit and a wave of forced selling once stimulus has ended later this year. That will create an opportunity to buy prime assets at discount prices in 2021 and 2022, setting up extraordinary gains for investors for an extended period. The best returns are likely to be found in urban real estate, not public equities, fueled by rising operating performance as the young people who fled the COVID-19 pandemic move back into the city and go back to work.

I will write more in later posts about how to construct the far-from-equilibrium analytical model described above.

Selected References

Atkinson, R. M., M.; Whiton, J. (2019). The Case for Growth Centers: How to spread tech innovation across America. Retrieved from Washington, D.C.:

Autor, D. (2019). Richard T. Ely Lecture. Work of the Past, Work of the Future. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109, 1-32. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191110

Bak, P. (1996). How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organized Criticality. New York: Springer Verlag.

Baker, S. R. B., N.; Davis, S. J.; Terry, S. J. (2020). COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty. Working Papers, (26983). Cambridge, MA.

Barabasi, A.-L. (2002). Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means. New York: Perseus Publishing.

Barábasi, A.-L. (2002). Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What it Means. New York: Perseus Publishing.

Bettencourt, L., Lobo, J., Strumsky, D., & West, G. (2010). Urban Scaling and Its Deviations: Revealing the Structure of Wealth, Innovation and Crime across Cities. PLoS ONE, 5(11), 1-9. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013541

Bettencourt, L. W., Geoffrey. (2010). A Unified Theory of Urban Development. Nature, 467, 912-913.

Bloom, H. K. (1997). The Lucifer Principle: A Scientific Expedition into the Forces of History. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Buhayar, N. (2020, 12/21/20). The Work from Home Boom Is Here to Stay. Get Ready for Pay Cuts. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-12-17/work-from-home-tech-companies-cut-pay-of-workers-moving-out-of-big-cities

Cairncross, F. (1997). Death of distance: how the communications revolution will change our lives. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Camus, A. (1975). The Plague. New York: Randon House.

Cartwright, F. B., Michael. (1972). Disease and History. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Cohn, S. (2007). After the Black Death: Labour Legislation and Attitudes Towards Labour in Late-Medieval Western Europe. The Economic History Review, 60(3), 457-485. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4502106?seq=1

Crawford, R. H. P. (1914). Plague and Pestilence in Literature and Art. Oxford: Clarendon.

Daalder, I. J., Will; Kling, Samuel. (2021). Why We Don’t Believe the Big City Obituary. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-02/new-survey-shows-big-cities-aren-t-dead?sref=oolPz7y9

Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies. New York: Norton.

Duranton, G. P., D. (2004). Micro-foundations of urban agglomeration economies. In H. V. T. J-F. (Ed.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2119-2171). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Ehrenhalt, A. (2013). The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City. New York: Random House.

Epstein, J. M. (2013). Agent_Zero: Towards Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Florida, R. (2012). How and Why American Cities Are Coming Back. Bloomberg CityLab. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-05-17/how-and-why-american-cities-are-coming-back?sref=oolPz7y9

Florida, R. (2020). This Is Not the End of Cities. Bloomberg CityLab. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-06-19/cities-will-survive-pandemics-and-protests?sref=oolPz7y9

Gilbert, N., & Troitzsch, K. G. (2005). Simulation for the Social Scientist. New York: Open University Press.

Giuliano, G., Kang, S., & Yuan, Q. (2019). Agglomeration economies and evolving urban form. The Annals of Regional Science, 63, 377-398. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00168-019-00957-4

Glaeser, E. L. G., Joshua D. (2009). The Wealth of Cities: Agglomeration Economies and Spatial Equilibrium in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(4), 983-1028.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of Knowledge in Society. In Individualism and EconomicOrder. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books, Random House.

Kempes, C. W., Geoffrey. (2020). The Simplicity and Complexity of Cities. The Bridge: Linking Engineeering and Society, 50(4).

Kotkin, J. (2000). The new geography: how the digital revolution is reshaping the American landscape. New York: Random House.

Koyama, M., Jedwab, R., & Johnson, N. (2019). Pandemics, Plagues, and Populations: Evidence From the Black Death. Discussion Papers, (13523). London.

Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing Returns and Economic Geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99, 483-499.

Krugman, P. (1996). The Self-Organizing Economy Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

Leonard, D. (2020, 12/21/20). New York Misses You. Bloomberg Businessweek, 45-49.

Lotka, A. J. (1956). Elements of Mathematical Biology. New York: Dover.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan.

McNeill, W. H. (1996). Plagues and Peoples. New York: Doubleday.

Minsky, H. P. (1992). The Financial Instability Hypothesis Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=161024

Paybarah, A. (2020, 5/16/20). Where New Yorkers Moved to Escape Coronavirus. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/16/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-moving-leaving.html?auth=login-email&login=email

Quealy, K. (2020, 5/15/20). The Richest Neighborhoods Emptied Out Most as Coronavirus Hit New York City.New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/upshot/who-left-new-york-coronavirus.html

Ricardo, D. (1817). The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1 ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

Romer, P. (1986). Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002-1037.

Romer, P. (2020, 3/23/20). Will Our Economy Die From Coronavirus? New York Times.

Romer, P. F., Brandon. (2020). How to Avoid an Economic Catastrophe [Interview]. City Journal. Retrieved from https://www.city-journal.org/how-to-avoid-an-economic-catastrophe

Rutledge, J. (1981). Why Interest Rates Must Fall in 1982. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1982a). Decision Makers Now Confront Disinflation. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1982b). Ghost Town. New York Times.

Rutledge, J. (1982c). What Lower Yield on Tangibles Means. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1983). The Structural Deficit Myth. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1984). Don't Fear a Relaxed Fed Policy. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1985a, March 6, 1985). The Big Bad Deficit. It's Not the Problem. Fortune.

Rutledge, J. (1985b). Forest Fire of Disinflation. Financial Times.

Rutledge, J. (1986a, March 31, 1986). The Economist Who Says Inflation is Dead. Fortune.

Rutledge, J. (1986b). The Tax Bill's Deflationary Impact. Wall Street Journal.

Rutledge, J. (1986c). We're Fattening Up the Financial Markets. US News and World Report.

Rutledge, J. (2015). Economics as energy framework: Complexity, turbulence, financial crises, and protectionism. Review of Financial Economics. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2015.02.003

Rutledge, J. (2020). Syllabus: Far-from-Equilibrium Economics and Finance.

Rutledge, J. (2021, 2/15/21). Far-From-Equilibrium Economics and Finance.

Shakespeare, W. (2001). All’s Well That Ends Well. Raleigh: Alex Catalogue.

Shakespeare, W. (2008). Twelfth Night (R. Warren Ed. Vol. Act 5, Scene I, Lines 264-275). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shakespeare, W. (2011). The Taming of the Shrew. Guilford: Saland.

Shakespeare, W. (2017). Romeo and Juliet. London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare.

Slack, P. (1985). The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Berlin: W. Strahan, and T. Cadell.

Snowden, F. M. (2019). Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Solé, R. V. (2011). Phase Transitions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sornette, D. (2003). Why Stock Markets Crash. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Strassler, R. B. (Ed.) (1996). The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. New York: The Free Press.

UN-Habitat. (2010). State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011 — Cities for All: Bridging the Urban Divide. Retrieved from New York: http://www.unhabitat.org

UN-Habitat. (2020). Global State of Metropolis 2020 – Population Data Bookle. Retrieved from New York:

Wilensky, U. (2021). NetLogo. Evanston IL: Northwestern University. Retrieved from https://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/

Zinsser, H. (1934). Rats, Lice and History. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Just as the UK and Holland invented the corporation as a holding tank for value left over after South Sea bound ships returned with spoils, sold them off and liquidated the proceeds (ships as the SPVs of the 17C) ... corporations are now being deconstructed (balance sheet DeFi) ... the post-covid City has become a work of the imagination and it may well be filling that gap.

But a city is tangible, not just an idea but also a living, physical balance sheet. Like all idealized balance sheets, it needs a mix of liquid and physical capital. It needs a steady or growing stream of tax receivables (which means happy citizens) shored up by investments in its physical capital. It needs leverage but not too much, and common equity spaces that make life more than a factory with absentee owners for its residents. Green patches not just for animal grazing but also people grazing and gazing. And, it should not have too many contingent liabilities. IE., sufficient thought should be given to design that the byproducts of urban living are planned for and integrated into asset renewal. For, a city is at the end of the day an idea that attracts and inspires people. Its citizens may be off the balance sheet, as labor, innovation and imagination are off the corporate balance sheet, but the relationship between the city balance sheet and its citizens is inextricable. A city without people has no assets.