Part 1 of 2: COVID and Urbanization. Cities hit hard by COVID. Review of historical, Economic and Scientific Literatures

The impact of COVID-19 on Urban Real Estate: historical, economic and scientific evidence explain why they'll be back

Note to subscribers: This is the first half of a longer white paper that I wrote for Safanad to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the population and growth of cities and outline our approach to thinking about commercial real estate investing for the post-pandemic economy.

You can download a PDF file of the full paper, including all of the references, by clicking here.

In this post, I examine three approaches: 1) the historical record of pandemics and cities; 2) the economics literature on urbanization; and 3) the scientific literature on the forces behind urbanization. All three point to the conclusion that the death of cities have been overrated. This sets up an investment thesis for acquiring commercial urban real estate. In the second half of the paper, which I will post tomorrow, I will describe the economic framework I use to develop a post-pandemic investment strategy and give you some idea of the thing and duration of the recovery period.

SUMMARY

Cities bore the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, many people fled the city for safer, less crowded locations. Some argue that people will never return to the cities. A careful review of the historical record and of two separate bodies of academic research show they are wrong. Throughout history, the productivity advantages of living and working in cities have made them magnets for young, energetic, creative people. It will take time, but cities will return stronger than ever, as they have after every pandemic in history.

Cities were the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more cases and more deaths than outlying areas. Frightened city dwellers—those who could afford to do so--abandoned the city and moved their families to safer, less crowded suburban and rural locations. A review of historical pandemics strongly suggests they will return once the danger has subsided.

For the reasons why cities are so resilient, I review two different bodies of research. First, a half century of economic research shows that cities exhibit economies of scale, known as agglomeration economies, that make people in cities more productive than they are in less densely populated areas.

Second, recent research in complex adaptive systems by theoretical physicists at the Santa Fe Institute shows why cities exhibit economies of scale. Like networked organisms in physical science, cities exhibit superlinear scaling properties. That means doubling the size of a city more than doubles the major measurable characteristics of a city, including income, wealth, innovation, creative activity, the birth and death of businesses, crime, garbage, and the spread of diseases. “On average, as city size increases, socio-economic quantities such as wages, GDP, number of patents produced, and number of educational and research institutions all increase by approximately 15% more than the expected linear growth...That 15% productivity advantage is true for all cities, in all countries, in all time periods where there is adequate data”.

That superlinear scaling law is the reason why cities were initially hit harder than the countryside by COVID-19; it is also why cities will come back faster than the countryside once the disease has been tamed.

CITIES BORE THE BRUNT OF COVID-19

The table below, compiled by the United Nations, shows that in every major country, COVID-19 hit the people who live in large cities especially hard. For example, based upon UN data through July, 2020, 82% of the 4,748,806 cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. were recorded in just the four largest cities plus Washington, DC. (UN-Habitat, 2010). Other countries had the same experience.

It makes sense that people in cities are more likely to be in sneezing-distance of each other than are people who live in the suburbs or countryside. It also makes sense that those who could afford to do so fled the city when COVID hit to protect themselves and their families from the virus. Those who could not afford to leave stayed.

Frightened People Fled the City to Escape COVID-19

According to a New York Times analysis of cell phone records, 420,000 people moved out of New York between March and June of last year; 137,000 people (including more than one of my partners) filed with the Post Office to have their mail forwarded to addresses outside the city in March and April (Paybarah, 2020).

Of course, not everyone can afford to leave town. Data shows that fleeing the city is a luxury good, as it has been throughout history. In the chart above, cell phone records show that one in three high-income families left town while the bottom 80% of earners largely stayed put (Quealy, 2020).

They haven’t yet returned. Data on office card swipes from as recent as December 2020 show that only one in seven office workers in San Francisco and New York have returned to work. Not surprisingly, rent per square foot of office space has declined in both cities.(Leonard, 2020).

Some say that frightened residents, now that they have learned to work from home and communicate with colleagues on Zoom, will never come back to the city (Baker, 2020). “There’s going to be a reverse of the urban boom, ” according to Stanford economist Nick Bloom (Buhayar, 2020). Both the historical record and the scientific literature say they are wrong. Major cities will be back stronger than ever.

Historical Record

A tour of my bookshelf would show that I have a longstanding interest in systems biology, epidemiology, and the history of plagues, with off-putting titles like Elements of Mathematical Biology (Lotka, 1956), Plague (Camus, 1975), Plagues and peoples (McNeill, 1996), Disease and History (Cartwright, 1972), Rats, Lice and History (Zinsser, 1934), The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (Slack, 1985), and Guns, Germs and Steel (Diamond, 1997) along with a score of books on the agent-based models used to model the dynamics of disease transmission (Epstein, 2013; Gilbert & Troitzsch, 2005; Wilensky, 2021). To me, plagues and pandemics are real-world manifestations of my real intellectual passion complex adaptive systems and far-from-equilibrium physics, where interactions among agents, not the decisions of an individual agent, drive all major change, including changes in asset prices. I will discuss these ideas later in the text. Go ahead, call me a nerd.

There have always been plagues and pandemics. Many were far more deadly than COVID-19, as documented in the chart below.

Examples include:

the Plague of Athens in 430 BC that altered the course of the Peloponnesian War, described by Thucydides, who was himself stricken (Strassler, 1996)

the Plague of Justinian in 541 AD that killed 30-50 million people

the Black Death of 1347 that killed 200 million people, half of Europe's population (Koyama, Jedwab, & Johnson, 2019), inspired Boccaccio to write Decameron (1351), provided the setting for many of Shakespeare’s plays (2001, 2008, 2011, 2017), and likely hastened the end of feudalism (Cohn, 2007)

Smallpox (1520 onwards) that killed more than 50 million people in Europe and wiped out both the Incan and Aztec civilizations (Snowden, 2019)

the Great Plague of London in 1665 that drove Isaac Newton from Cambridge to the countryside where he invented differential calculus and the theory of optics and formulated the law of gravity

the Spanish flu of 1918 that infected over one third of the world's population and killed 40-50 million people

In each of these examples, people were terrified and those who could fled cities for the countryside. Their intense experiences were memorialized in art and literature (Crawford, 1914). In each of these examples they moved back to the city once the pandemic had subsided (Snowden, 2019). What made them come back?

Over long periods, the forces driving increases in urbanization have proven powerful enough to overcome people’s fears and bring them back to the city. After countless pandemics, wars, and other disasters, 85% of people in High-Income countries live in urban areas today. The United Nations predicts that the global urban population will grow by more than one billion people in the next 15 years, as shown in the table above (UN-Habitat, 2020).

There are many reasons why people come back to the city but foremost among them is that people living in cities are more productive and creative. Countless academic studies have shown that cities exhibit economies of scale.

Two separate bodies of academic literature, in economics and in physics, help us understand why cities are so resilient. The first is the literature on agglomeration economies developed by labor economists. The second is the literature on superlinear scaling in complex systems developed by theoretical physicists at the Santa Fe Institute. Taken together, they help us understand why cities exhibit economies of scale.

Economies of Scale in Urbanization: The Economics Literature

There is a long history in economics of writing about the productivity benefits from specialization of labor in cities, going back to Adam Smith’s (1776) pin factories, David Ricardo’s (1817) comparative advantage, and Alfred Marshall’s (1890) analysis of the textile industry.

The economics literature focuses on the microeconomic factors—today we would call them externalities—that make people and businesses in urban areas more productive, such as specialization of labor and capital, job matching, labor pooling, short supply lines, shared suppliers, and shared knowledge. Labor economists refer to them, collectively, as agglomeration economies.

There is broad agreement among the group of labor economists known as urbanists, including two with Nobel Prizes (Krugman, 1991; Romer, 1986) that agglomeration economies are significant in urban areas. The causes of agglomeration economies are articulated by Duranton and Puga (2004). For a review of the empirical evidence, see Glaeser’s (2009) encyclopedic literature review citing 130 studies, itself cited 348 times by other authors, and the more recent literature review by (Giuliano, Kang, & Yuan, 2019).

In the 1980s, a group of dissenters, known as suburbanists, argued that the growth of information technology and consequent reduction in information costs would change all that, make distance irrelevant, erode agglomeration economies, and reverse the growth of cities. (Bloom, 1997; Cairncross, 1997; Kotkin, 2000). As the UN data reported in Figure 5 above show the urbanists prevailed; cities have continued their march toward increasing density.

The consensus view today is that the driving force of urbanization is the fact that density speeds the transfer of knowledge and flow of ideas, illustrated by the fact that three-quarters of all U.S. venture capital investments in startup companies are made in just two metropolitan areas, the San Francisco Bay area and the Boston-New York-Washington D.C. corridor (Florida, 2020) (Glaeser, 2009). As reported by Florida (2012), this supports Ehrenhalt’s (2013) Great Inversion thesis that future urban in-migration will be dominated by affluent, educated professionals in their 20s and 30s, that will more than replace an outflow of people who are on average older, less-educated, and more likely to be recent immigrants. As Autor (2019) shows, this change in the demographic composition of urban populations increases the average education level of urban residents and supports rapid increases in urban incomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reopened the debate. Some, echoing the arguments of the urbanists in the 1980s, that advances in technology—in this case Zoom meetings—makes it no longer necessary for people to go to the office. They believe the exodus from major cities will be permanent (Baker, 2020). But the vast majority of recent studies supports the urbanist case that, once COVID-19 is safely behind us, the growth of cities will resume (Daalder, 2021; Florida, 2020; P. Romer, 2020; P. F. Romer, Brandon, 2020).

Nobelist Paul Romer(2020)sums up the evidence, “The underlying economic reality is that there is tremendous economic value in interacting with people and sharing ideas. There’s still a lot to be gained from interaction in close physical proximity. For the rest of my life, cities are going to continue to be where the action is.”

Economies of Scale in Urbanization: The Complex Systems Literature

Every serious study of urbanization begins by giving homage to Jane Jacobs’s classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), in which she described a city as a living organism where chance interactions among people in densely-populated urban neighborhoods are the source of creative activity and growth. And yet, with few exceptions (Krugman, 1996), the economics literature has failed to fully exploit her insights, focusing on static equilibrium conditions between economic agents, rather than viewing cities as complex, interactive, dynamical systems.

Recently, a group of theoretical physicists, led by Geoffrey West at the Santa Fe Institute, have applied the tools of complex adaptive systems to explore the dynamic behavior of cities over time. Their results provide overwhelming scientific evidence showing economies of scale in urbanization (Kempes, 2020).

In an influential paper published inNature, Luis Bettencourt and Geoffrey West(2010)of the Santa Fe Institute explore the source of urban economies of scale. They present new analysis of large, urban data sets covering hundreds of cities and urban centers in regions and countries across the world over many decades. Their results are summarized, below, in the graphic showing the relation between the relative population size of a given city to a wide variety of socio-economic metrics.

Interestingly, as shown in the graphic above, they find that the major characteristics of a city, including income, wealth, innovation, creative activity, the birth and death of businesses, infrastructure, crime, garbage, and the spread of diseases are all driven by population density according to the same, simple scaling law.

“On average, as city size increases, socio-economic quantities such as wages, GDP, number of patents produced, and number of educational and research institutions all increase by approximately 15% more than the expected linear growth. There is, however, a dark side; negative metrics including crime, traffic congestion, and incidence of certain diseases all increase following the same 15% rule. The good, the bad, and the ugly all come as an integrated, predictable package.” (p. 913).

That 15% productivity advantage is true for all cities, in all countries, in all time periods where there is adequate data. In other words, “cities are approximately scaled versions of one another.” (p. 913) This is similar to results in biology showing economies of scale in organisms and in communities like anthills and beehives, where continuous adaptation, rather than equilibrium, is the rule. (although there the scaling metric is closer to 20%).

Their results reflect the properties of the networks that cities depend on to supply the flow of energy and other resources needed to sustain life. For example, doubling the population of a city of any size requires only an 85% increase in infrastructure—roads, mass transit, parks, electrical power, or hospitals. The result is economies of scale in the growth of cities, the source of the productivity and economic growth advantages described in the economic studies cited in the previous section.

Their results show why large cities like New York were hit approximately 15% harder than small ones in the COVID-19 pandemic. And they show why large cities like New York will come back faster than smaller cities once the pandemic is behind us. The 15% productivity advantage can be viewed as a gravitational force that “acts as a magnet for creative and innovative individuals, and stimulants for economic growth, wealth production, and new ideas.” (p. 913).

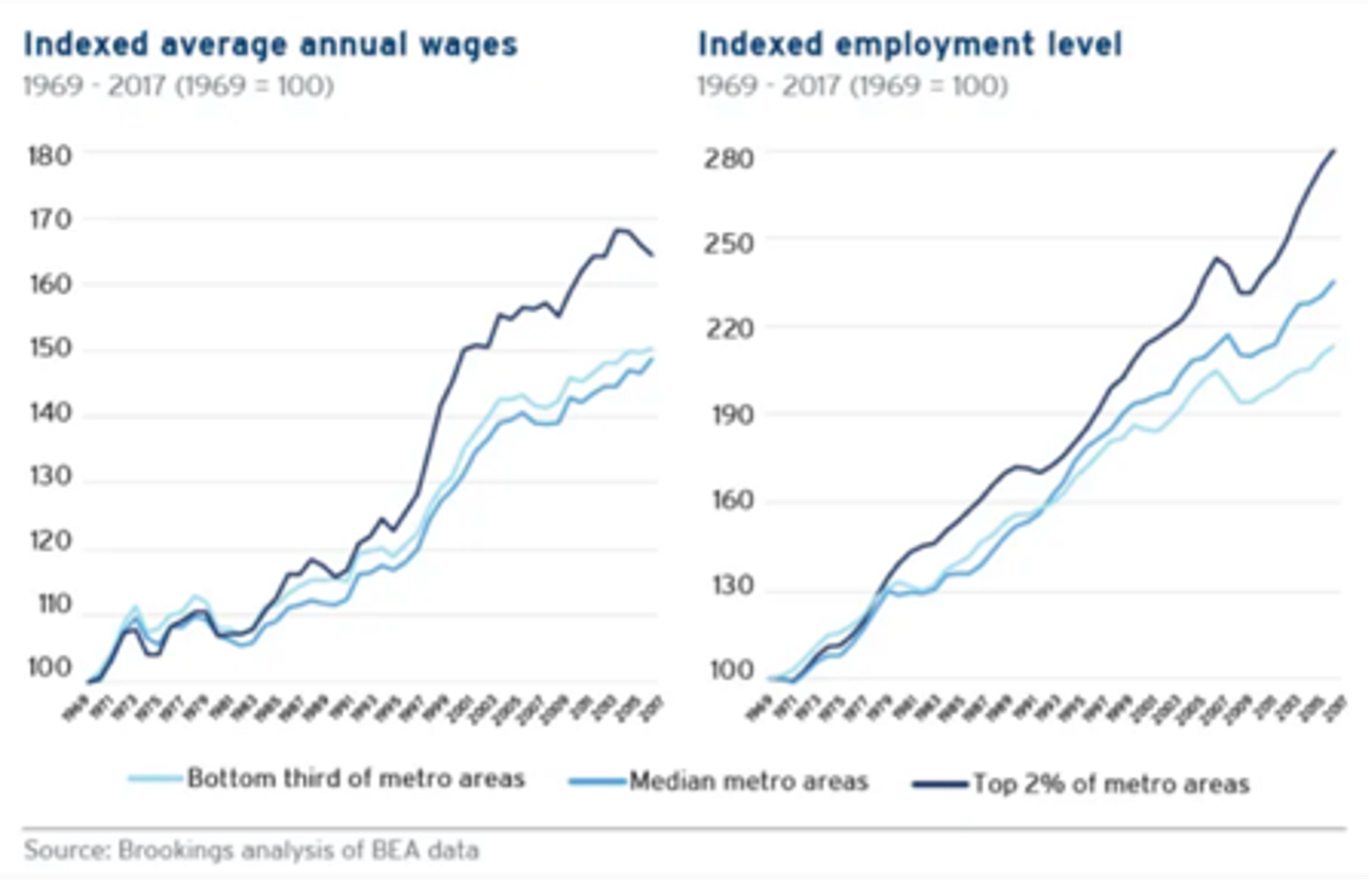

These results explain the economies of scale identified in the economics literature. Both wages and employment levels grow faster in large metro areas than small ones over time, as shown in the chart above (Atkinson, 2019). And the composition of cities changes with population density, with more high-skill and professional jobs and fewer low-skill jobs as density increases, an advantage which appears to be increasing over time, as shown in the chart below (Autor, 2019).

Before we leave this section, there is one more important result to point out. In a separate paper, Bettencourt, Lobo, Strumsky and West (2010) examined the performance of 360 U.S. metropolitan areas relative to the value predicted by the estimated 15% scaling law described above. They found that that some metropolitan areas (e.g., New York and San Jose) systematically outperform the scaling law and others (e.g., Detroit) systematically underperform the scaling law, likely representing local factors unrelated to population size, such as local geography, taxes and regulations and the like.

Interestingly, they find that the process describing the impact of local advantages and disadvantages displays long-term memory: “any initial advantage or disadvantage that a city has relative to its scaling expectation tends to be preserved over decades.” That fact gives investors important information about where to look for investments over the next few years as the economy rebounds from COVID-19 pandemic.

Summary: They’ll Be Back

So far, the analysis in this paper has focused on a single question: will cities ever be able to recover from the pandemic? Our conclusions are:

There is a reason--superlinearity--why cities like New York were hit harder than suburban or rural areas others during the pandemic.

That same reason will make people return to the cities once the pandemic is behind us, just as they have done for thousands of years. With apologies to Arnold, they’ll be back.

Historically relatively successful cities, like New York and the San Francisco Bay area, where local factors have made them outperform expected levels, will recover faster than other, historically less successful cities. Estimates show that outperforming cities will continue to be more successful than other cities for many decades into the future.

One implication for property investors is clear. As the economy recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, investors will be rewarded for focusing on urban property, not suburban or rural property, and they should focus on top quality assets in historically successful cities like New York and San Francisco, not chase apparent bargains in smaller, less historically successful areas.

Implications for Investors

In the remainder of this paper, I want to focus on a broader topic: how these conclusions fit into an overall investment strategy. That requires us to consider three issues:

the appropriate overall role of real estate in asset allocation,

which sub-sectors of real estate to focus on, and

the most complicated issue of all, when is the right time to make the investment.

Answers to these questions must be made in the context of an analytical framework capable of explaining the periods of growth punctuated by collapses into economic and financial crisis once or twice each decade that characterize developed economies like ours. I will describe such a framework below.

For reasons explained in depth in a separate article (Rutledge, 2021), accepted macroeconomic models of the sort taught in many PhD programs and used by the Fed and other central banks are disappointing in this regard. Their myopic fixation on explaining output and employment—the economy’s profit and loss statement—makes them unable to explain the much larger events taking place in asset markets—the economy’s balance sheet. And their worship of so-called micro-foundations has led them to characterize the economy as being in general equilibrium at all times, only being nudged away by temporary, gentle, normally distributed exogenous shocks.

The end product has been elegant models that do a poor job explaining the real world. For that reason, I have spent much of the past four decades developing an alternative framework designed to embrace asset market shocks and financial crises as normal events. In my next post, I will give you a brief summary of the logic behind my approach, how to apply it to understand the post COVID-19 economy and markets, and how to approach real estate investments in the post-pandemic economy.

NOTE to subscribers: This is the end of the first half of the full paper. You can read the second half of the paper, in which I describe the analytical framework behind our investment strategy and apply it to the post-pandemic period, by reading the next post. You can also download a PDF file of the full paper, including all of the references, by clicking here.