Last week we lost Robert Lucas, the brilliant economist who radically changed the way the macroeconomics does its work and the way central banks make decisions. I admire his contributions to economic theory immensely but, as you know, I am not a fan of where the macroeconomics profession has ended up today. I will write a serious piece about his enormous impact on ideas in a later piece. For today, I just want to write a personal note about the incredible circumstances in which I first met Bob Lucas a little over 50 years ago.

In the Spring of 1972, near the end of my second year in the UVA PhD program, I was chosen (I have no idea how, why, or by whom) to receive a Fellowship in Money and Banking for the work I was doing in rational expectations, which carried the princely sum of $5000 to do research of my choosing. (My total income that year was otherwise $7000). So I asked my dissertation advisor, Richard Selden, to see if he could arrange for me to spend the following year at the University of Chicago so I could have an adventure and learn at the feet of the masters.

When I showed up for the first day of classes at Chicago, I signed up to audit every class I could squeeze in at both the Economics Department and the Business School, including Zellner’s Bayesian course, Fama’s beginning finance class, Theil’s classical econometrics course, and Milton Friedman’s undergraduate micro course. But the high point of the week was 3PM on Tuesday’s when Milton Friedman ran his Monetary Workshop. When I walked in the seminar room for the first time, I nearly fainted.

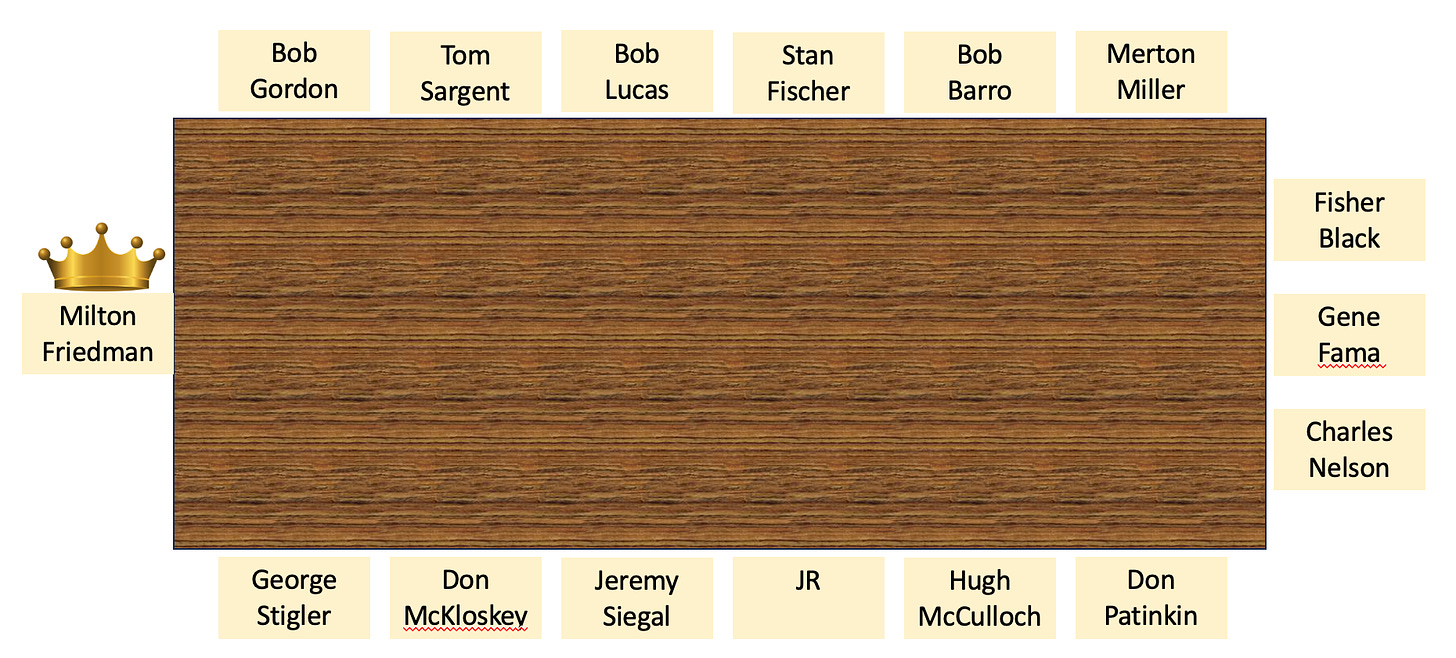

You can see who was sitting around the table in the graphic above. (Note: These are the ones I can remember; I know I am leaving several people out and apologize.) In the graphic, Jeremy Siegel, Hugh McCulloch and I are mere 3rd year students—all the others were already big shots at the time. Half a dozen of them now have Nobel Prizes—Fisher Black only missed out because he died too young to get the prize for the Black-Scholes Theorem (duh!) published later that year.

Milton Friedman sat at the head of the table where he clearly belonged. I crowned him king in the graphic because everyone else there treated him with such deference. Milton was, indeed, the king of macro at the time, or at least the king of his half of macro (Samuelson owned the other half). Not long before, he had published the paper that put inflation expectations at the heart of both unemployment and interest rate thinking.

Most of the guys around the table made careers out of clarifying, estimating, and extending Milton’s analysis. The guys on the north side of the table were focused on the idea that the impact of policy on output and employment depended upon whether or not people expected the policy change or were surprised by it. Lucas, their ringleader, had already written about John Muth’s seminal work in rational expectations. Years later, that work later morphed into what is now known as Modern Macroeconomics and is embodied in the Dynamic, Stochastic, General Equilibrium (DSGE) models used by all major central banks today. Its core assumptions are rational expectations, a rational representative agent, and an economy that is in, or close to, general equilibrium (i.e., full employment) at all times, only temporarily nudged away from equilibrium by random “shocks” and policy surprises.

I had the pleasure (torture?) of presenting papers to that workshop on two different occasions. My first effort was to present the theoretical model and preliminary empirical results for what was to become my dissertation, later published as A Monetarist Model of Inflationary Expectations. (You can download the PDF below). In that paper, I developed and tested the hypothesis that inflation expectations, as embodied in interest rates, are formed rationally, i.e., in a way that is consistent with the way a professional economist would form expectations. I remember being grateful that I survived the experience, and that Milton kindly stayed after the seminar to talk with me about my work and to show me how he used rolls of tracing paper held against the window to estimate the lags between money supply and the price level.

My second presentation was a year later when I, a newly minted Assistant Professor at Tulane University, was invited to present work I had done attempting to translate the mostly verbal work of Irving Fisher into a mathematical model of the business cycle. I later learned that the second appearance was a job interview; sadly, no job offer was forthcoming (heavy sigh!) My paper (below) was later published in the American Economic Review as “Irving Fisher and Autoregressive Expectations”.

The things I learned from these extraordinary people at Chicago launched me on a career with many adventures. I moved on from Tulane to Claremont Men’s College where I started a research institute to produce forecasts of interest rates, then served a couple of years as William Simon’s economics wingman, then did a stint in the White House working with my friend Larry Kudlow on the Reagan Economic plan. In later years, I burrowed my way into the financial markets, first by launching a family of mutual funds, then by serving as the in-house shareholder value farmer at Kelso, the pioneering private equity firm, then raising private equity funds of my own, and finally by helping my dear friend Kamal Bahamdan build the extraordinary global investment house known as Safanad.

After all that time, I still remember the kindness Milton Friedman, Bob Lucas, and the other members of the Tuesday Money Workshop showed to a 22 year old grad student presenting his first paper. May Robert Lucas Rest In Peace.

Dr. John