Inflation, Tax Rates, and Interest Rates

Tangible Assets, Financial Assets, and Asset Market Equilibrium

Summary: Contrary to the textbooks, interest rates are not determined by savings rates, budget deficits, or investment, or other flows of funds. They are determined by whether people want to own our $495 trillion stock of existing assets at current prices. That is driven, more than anything else, by what is happening to inflation and tax rates. Today, both are pushing investors to sell stocks and bonds and buy hard assets, a key reason for the ongoing bond market meltdown.

Why 1981 matters for 2022

In 1981, I wrote Why Interest Rates Will Fall in 1982 for the Wall Street Journal Op-Ed page to explain why zero inflation and lower tax rates in the Reagan Economic Plan would result in sharply lower interest rates and renewed economic growth. I would urge you to take a moment to read it to have a glimpse of economic issues from a different time, and would welcome your comments on the article.

At the time, economists were divided between those who argued that the Reagan Economic Plan would create massive budget deficits and drive interest rates up (the 30-year Treasury was a mind-numbing 15% at the time) and those who argued the tax cuts would unleash a gusher of personal savings that would drive interest rates down. I argued that both groups of economists were wrong.

In my view, interest rates are determined by the public’s willingness to own the stocks of assets that already exist, not by savings, budget deficits or investment. In 1981, I argued that the sharp drop in inflation over the previous 18 months, together with the Reagan tax cuts, would trigger a massive shift in asset demand that would both inflate financial asset prices, i.e., drive interest rates down, and deflate real asset prices, triggering waves of disinflation and a decade of corporate restructuring.

In a recent WSJ Op-Ed Richard Vigilante revisited my 1981 analysis and explained its relevance for today. The asset shift that began in 1981 caused an upheaval in U.S. capital markets that produced a four-decade long bull market in stocks and bonds.

Over the past year, high inflation and rising tax rates have thrown these portfolio shifts into reverse, ending the bull market and threatening to unwind the gains of the past 40 years. In these conditions, it makes sense for investors to increase allocations to real property and other tangible assets reduce exposure to financial assets.

One Law of Economics

There is only one positive statement in economics. Some call it the law of one price (LOOP). Some people call it arbitrage. Some call it “buy low, sell high.” And some even call it by its proper name, the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Whatever you call it, economics is built on the idea that people, when presented with two prices for the same good or service, will buy at the lower price and sell at the higher price, driving them together to a single price that we reverently call equilibrium. IMHO, any statement that you cannot reduce to simple arbitrage is not economics at all. The rest is all decoration.

Two economies

So, what did economists get wrong in 1981? They missed the elephant in the room, America’s massive balance sheet. As I will argue below, they are still having trouble locating the elephant today.

When economists write about the economy, they typically mean GDP, the value of goods and services of goods and services produced over a year. This year, for example, US GDP will be about $23 trillion.

Macroeconomics textbooks explain GDP with the metaphor of an island economy shown in Figure 1. On our island, there are two people. John catches fish, Pamela picks coconuts and they exchange fish for coconuts for dinner. We can put together a set of accounts to measure our island’s GDP, expressed as either fish per year (fish/year) or coconuts per year (coconuts/year) by adding the total number of fish and coconuts produced using the relative price from their exchanges.

But there is a second economy that we have to understand before we can say anything useful about GDP—the balance sheet economy. Without the volcano it sits atop there would be no island, no tree, no coconuts. Without the stock of fish under the water there would be no catch of the day. Both represent the island economy’s capital stock. I think of capital as stockpiles of stored energy that can be transformed by current labor into useful output.

Countries measure GDP the same way, by putting together a set of national income accounts that measure the value of all of the goods and services produced during a year. National income accounts play the same role for a country as a Profit and Loss statement (P&L) does for a business. Both summarize the flow of activity during a year, which is why they are expressed as ($/year). It should be obvious that any metric expressed per unit of time is simply a measure of speed, like miles per hour for your car. That makes GDP simply a measure of how fast we are producing things, how fast we are earning our incomes, and how fast we are transforming the stored energy we call capital into useful output.

Balance Sheets are huge

Just as every business has both a P&L and a balance sheet, every country has both national income accounts and a balance sheet. A country’s balance sheet is a snapshot, taken at a moment in time, of the stuff that we own and owe each other, our assets, liabilities, and net worth. For both a country and a business, we need to understand the P&L and the Balance Sheet to say anything useful about its future performance.

The balance sheet is the elephant in the room.

The most important thing to know about the US economy’s balance sheet is that it is huge compared with annual GDP. According to the Fed’s most recent Z1 report, US total assets were valued at $495 trillion on 12/31/21, more than 23x this year’s $23 trillion GDP. (Actually, the value of total assets is severely understated. The federal government’s balance sheet, for example, does not include the value of the more than 700 million acres of land they own.)

The magnitude of total assets relative to pretty much anything else means that, over short periods, we can think of the stock of existing assets as given—a fact of history. It is so big that even small percentage changes in the composition of the balance sheet can produce tsunamis of dollars that overwhelm changes in GDP components in a given month, quarter, or year.

Balance Sheet composition

The composition of assets in our national balance sheet is the key to understanding interest rates. Figure 2, below, shows that in the US, on 12/31/21, people held $495 trillion in total assets. They held $154 trillion, or 31% of total assets in the form of tangible assets. What are tangible assets? Some people call them real assets or hard assets. They are our natural resources (land, timber, oil reserves, etc.) plus all the factories, machines, cars, tractors, houses, and other durable goods that we produced in the past but haven’t completely used up yet. If you can see it from an airplane window, it’s probably a tangible asset.

Cars and houses are two good examples of tangible assets. In the U.S., during 2021 we produced 14.5 million new vehicles, but according to the Census Bureau, there were 284 million cars and trucks already on the road, i.e., there were 20 used vehicles on the road for every new car produced during the year.

The same goes for houses. The Census Bureau reports that there were 142 million existing housing units in June, 2021 and that we produced just 1.4 million new homes during the year, i.e., there were 106 existing homes already in use for each new home built during the year.

To a first approximation, all cars are used cars and all homes are old houses.

Americans held the remaining $341 trillion (69% of total assets) in the form of financial assets, including $311 trillion (63%) in privately-issued financial assets like stocks, corporate bonds, and bank accounts, and the $30 trillion (6%) in government-issued securities like T-bills and Treasury bonds that we lovingly refer to as the national debt.

As the Fed’s Z1 report explains, the Fed has historically taken the view that our net worth is roughly equal to the value of tangible assets because, to a first approximation, every financial asset that one person owns is offset by a liability of equal value that another person owes. As an example, the mortgage on your house is both your liability as the homeowner and an asset of the bank, insurance company, or pension fund that owns it. Together, they have no effect on our total net worth.

Asset prices, interest rates demand-determined

Each asset on the balance sheet has a market price, determined by supply and demand. (I know, duh!) Supply—the physical stock of assets—is almost perfectly inelastic (unresponsive to price) in the short run because, as I explained above, our annual production of new tangible assets (new machines, new cars, new homes) and our annual production of new financial assets (new mortgages, new bond issues, newly-issued shares) are vanishingly small compared with the stocks of assets that already exist.

The demand side, however, is not fixed. Each investor is free to divide his or her net worth among different available assets (and liabilities) in any way he or she chooses, presumably based upon relative expected after-tax returns and risks. It follows that asset prices on any given day are almost entirely demand-determined, i.e., prices will go to whatever level they need to be to make investors content to hold the available stock of assets, as James Tobin told us long ago. This is true for stocks, for bonds, for houses, for used cars, and for commodities like gold, diamonds, and copper. And it is just as true today as it was in 1981.

Once we know bond prices, we also know interest rates—given one you can calculate the other. That means the only thing that matters for determining the level of interest rates today is whether people are still willing to hold the mix of tangible and financial assets they owned yesterday at current prices.

It follows that asset prices will only change when people change their minds about the mix of assets they want to hold. And that will happen when people get new information about the likely after-tax returns and risks of different assets.

Inflation and tax rates key interest rate drivers

As I argued in 1981, inflation and tax rates are key drivers for asset mix decisions because they have different impacts on the after-tax total returns on real and financial assets. In 1981, both inflation and tax rates were falling. Falling inflation reduces the total return on real assets like houses and collectibles because the inflation rate of a tangible asset is a measure the capital gains component of its total return.

Likewise, falling tax rates increase the after-tax return on financial assets like stocks and bonds relative to the return on tangible assets because financial asset returns are generally reported to the IRS and tend to be fully taxed, while tangible asset returns are often either favorably taxed (oil, gas, real estate) or not taxed at all (the value of living in your home and the unreported increase in its market value).

Together, I argued in 1981, falling inflation and lower tax rates would cause people to attempt to sell real assets and buy financial assets, which would both deflate the prices of real assets and inflate the prices of stocks and bonds, pushing interest rates lower. I say attempt to sell because individual investors trying to sell real assets to buy more stocks and bonds won’t be able to do so at current prices because the other investors got the same memo and are trying to do the same thing. What gives, of course, is asset prices. Real asset prices fall, and financial asset prices rise until people change their minds. enough to make markets clear.

Measuring the asset shift

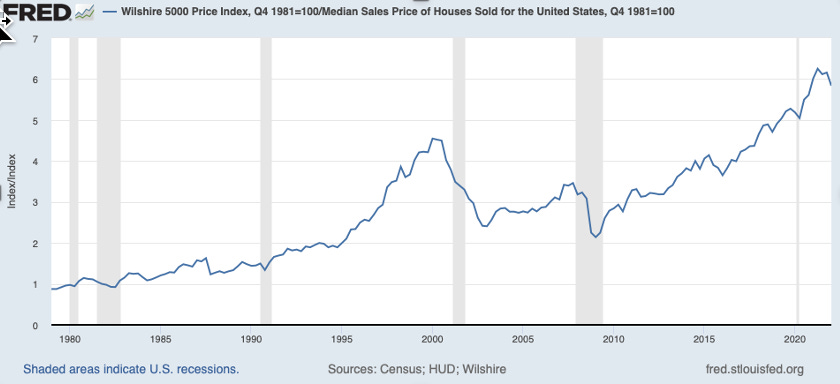

You can see what those changes meant for investors in Figure 3, below. The chart is a rough measure of the relative price of financial and tangible assets, which I have calculated by dividing the price of the Wilshire 5000 Index by the median sales price of a house in the US. I have based the series to equal 1.0 in Q4/81 when I wrote the WSJ article. You can think of the exercise as creating a basket of stocks worth just enough to buy exactly one house in Q4/81 and measuring how many houses you could have bought with that same basket of stocks at different dates since then.

Over the 40-year period shown in Figure 3, except for the dotcom bust in 2001 and the subprime crisis in 2008, stock prices rose faster than home prices. The same basket of stocks that could buy one house in December 1981 could buy six houses today.

The Fed’s Z1 report shows that over this period households and nonprofits shifted 7.1% of total assets out of tangible assets (houses), and into financial assets (stocks and bonds). That 7.1% shift in the composition of assets shifted $35 trillion from real property into stocks and bonds, which explains how we could have rising budget deficits and falling interest rates at the same time. As a result, bond yields fell from 15% in 1981 to near zero by 2021.

Falling rates are over

Why does this matter? Because we all know now that the four-decade period of falling inflation, falling tax rates, and falling interest rates shown in Figure 3 is over. Today, the same forces are at work, but in reverse—both inflation and tax rates are rising. As a result, after-tax returns on tangible assets have increased relative to financial asset returns, convincing investors to shift assets out of financial assets like stocks and bonds into tangible assets like real estate, just as they did in the 1970s. This has already pushed stock and bond prices sharply lower (interest rates higher) this year and inflated the prices of houses and other tangible assets. These price changes will continue if inflation stays near current levels and will only end when after-tax real and financial asset returns have been driven together again. Until that happens, you can expect real assets to outperform equities.

Navigating through today’s complex situation makes investing extremely difficult. In addition to the basic issues of taxing, spending, and printing money, we have to contend with Quantitative Tightening, Russia/Ukraine, China/Taiwan, polarized politics, food and energy shortages, supply chain hairballs, and the aftermath of COVID. I will write about each of these issues in turn in the coming weeks.

In my next post I will give you a visual way to think about how budget deficits and the national debt affect interest rates and stock prices. I think you will be surprised by the result.

JR

I have fond recollections of sitting and talking (mostly listening) with you at the Gilder Telecosm conferences where we were both speakers and you introduced me to thinking of economics using the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Your ability to simplify the complex and teach economics as it should be taught everywhere (visually) is rare if not unique. When someone truly understands a subject they distill it to simple elements - those who don't, or have ulterior motivations, strive to make it complex.

I've tried to follow your lead in my writing. I shared a paper a few weeks ago that I first published last May on my Linkedin page. I think you will find very interesting. Advancements described by Moore's Law reduced the cost of information - some suggest by a billion fold during the last 40 years. The paper addresses why the continuation of this vast economic benefit has dwindled if not died. This is not to suggest there won't be advances in technology coming our way - there will, but they will come much more slowly and be driven by different things that are not entirely visible outside a small circle.

Thank you, Paul McWilliams

"IMHO, any statement that you cannot reduce to simple arbitrage is not economics at all. The rest is all decoration."

Yep. I sometimes feel economics gets crushed by its own weight and suffers the fate of philosophy, leading to discussions about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. This is a great article that explains well how these forces of inflation and tax rates change preferences.